Interview: Melissa Hill | Fairfax, Virginia, USA

Melissa Hill is an artist living and working in Fairfax, Virginia (USA). Her work openly addresses the difficult themes of death and loss, often through the creation of non-narrative sculptural forms. She is currently earning her Masters of Fine Arts at George Mason University.

Artist Statement: "Artworks can be a reflection of the accumulation of events that have occurred in an artist’s life. I approach all of my pieces through this type of interpretative lens, and it is therefore a major driving force behind my work. In keeping with this concept, my work concentrates on interrogating the confluence of issues that most people would rather leave untouched. Perhaps this is most evident in the way my works interrogate and engage death and its inevitability. The aftermath of death remains a great mystery to us, a veil that cannot be penetrated even with our technological prowess and scientific advancements. I try to mold that mystery into a form, creating a tangible representation of an intangible concept..." Read More.

Emma Drew: You are very forthright about your personal experiences of the death of loved ones influencing your work, but I'd be curious to know if those events served as a main impetus in beginning your practice or if they became more of a focus once you had already started developing as an artist. Basically, what do you see as some of the origins of your work?

Melissa Hill: My high school career started out pretty normally, but by my junior year I had lost three people on the maternal side of my family that were really important to me. Because of this, I started to withdraw into myself and eventually I had a huge falling out with most of my friends who didn’t understand why I was acting the way I was. I think that’s about the time that I really started to delve into art. I started with illustrating stories from my childhood, but also did some painting and assemblage sculpture. A frequent subject in my work back then was the myth of Icarus. I was fascinated by the story of someone who wanted to stretch their wings and escape from their current situation. I wanted to fly away, but the story of Icarus is sobering: in his pride he flew too high and fell to his demise. I probably felt some resonance between his situation and mine--both captured in a reality that we didn’t want to be in. But unlike him, I knew that eventually all realities have to be faced. So while my art was my wings, I never fooled myself into believing that it would allow me to really get away from my problems, it just helped me to cope with them.

ED: Since you so openly concern your practice with death and loss, is your work meant to be palliative, for you or your viewers? Or perhaps meant as a part of the grieving or healing process?

MH: I would have to say that my work is both an analgesic and simultaneously something that is meant to facilitate the healing process for myself and hopefully viewers. I feel that, at the very root, when people are gone there is a hole left where they once were. Try as we might to fill that void with things or memories or events, it’s not possible to completely erase it. As such, I think that any attempt to “cure” the woes of those who have lost is foolhardy at best and fundamentally damaging at worst. I see my works as windows through which we can engage and touch the pain of the past, not to forget it, or to alter it, but to learn from it and grow.

ED: Do you think of your finished work as itself in process rather than as stand alone objects?

MH: Heraclitus said that we could never step twice into the same river, and I see art in the same way. We never approach the same work with the same perspective, and because of this, I feel that art is in a constant state of contingency. I make meaning when I create a work, but the viewer invests that work with a completely new meaning.

ED: How or why do you find these types of sculptures, from this year (non-narrative, non-representational) appropriate for the ideas you're exploring? How do their formal elements play into thematic concerns?

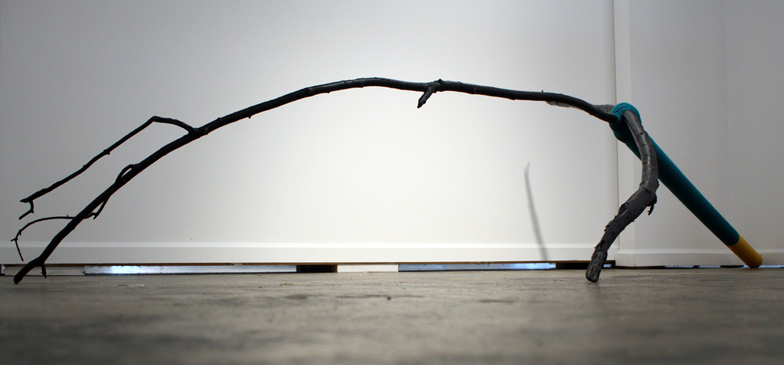

MH: I think that the non-narrative, non-representational aspect of my works is what really drives home the point about death and the human element that interacts with it. Death is a veil, a shroud behind which lies perhaps the greatest mystery we will ever encounter. People run from it, run towards it, cower in the site of it, plead to escape it, and long to embrace it, but in the end, we don’t know what it looks like or what is on the other side of it. To me, death is the place where narratives stop and narratives start, but since I cannot see beyond the shroud I have no reference upon which to build those narratives. In much the same way, I cannot give it a meaningful representational form. And so my works are made manifest through my own anxieties and anxieties that I think everyone feels at some point or another.

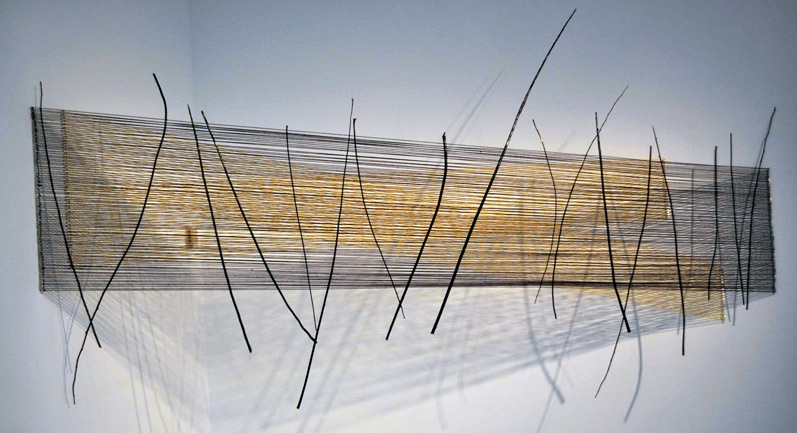

Perhaps the most important aspect of this is the light and the shadows and the space outside of the space. The space between the viewer and the work is something like the space between their now and their end. We don’t know when the end will come, bends and shadows block our view, but we know it comes nonetheless. The light and the shadows represent the world in which we walk, our faces held up towards the light for as long as possible, as the shadows of what will come slowly spread out beneath the surface.

ED: You seem interested in futility, or human attempts that are ultimately rendered futile (ie, immortality, bringing those gone back to life, creating "life everlasting"). The title "Tilting at Windmills," blatantly suggests a Quixotic level of delusion. How do we move forward in the face of such (known) futility? Do you think art plays a role in our persistence, even against stacked odds?

MH: I think that art can do both. I will be the first person to acknowledge that I am an escapist. I read to escape, I play games to escape, I create to escape. In my opinion artwork can help us escape, but we have to understand that escaping is not dealing, it’s not coping, and it’s not facing. I think the burden of using art as a tool for perseverance or to perpetuate a false reality falls on the viewer. In the end we can only take from a work the things that we desire to take from the work.

ED: How do you feel your work has changed in the past few years?

MH: I think that when I first started school I was ill equipped as an artist to deal with the subject matter that I wanted to deal with. I felt as though I danced around issues and only superficially interrogated the topics that I wanted to approach. Last year I decided that no matter how hard things became, I would use my artwork as a way to pour out my feelings, to give them a physical manifestation that would be impossible for me to ignore. Two years ago I couldn’t even tell someone that my work dealt with death; today I understand that my work not only deals with death and a sense of loss, but with the crippling fear and understanding that the deaths and losses that I have experienced will eventually be added to. To me, my work is cathartic. I won’t say that I’m more comfortable in my own skin than I was two years ago, but I’m certainly more confident that my artwork more aptly reflects my internal universe.

ED: In tandem with the previous question, do you know what's next?

MH: I would regret to say that I will “move on” from the emotional turmoil that has informed my work so far, but I feel that after the outpouring that I’ve undergone I am better prepared to explore new epistemological and ontological processes. I think that I will continue to reflect inward and continue to extract personal narratives in my future work, but I feel as though I am poised on the edge of something new and I find it to be quite exciting. I have spent a lot of time thinking about the telling of tales and the memories of stories being told, and I think that my future work will perhaps reconstruct to the memories of those narrative processes in a tangible form.

Emma Drew is a museum educator and server living in San Francisco. She graduated from Wesleyan University in 2010, where she studied European philosophy and literature and wrote a graphic novella about the Dust Bowl.

Emma Drew is a museum educator and server living in San Francisco. She graduated from Wesleyan University in 2010, where she studied European philosophy and literature and wrote a graphic novella about the Dust Bowl.