Interview: Imrana Tanveer | Karachi, Pakistan

Interview by Emma Drew

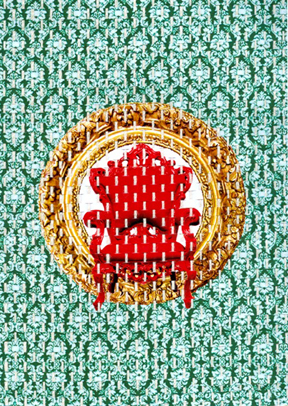

Imrana Tanveer is visual artist and writer based in Karachi. She holds degrees from the National College of Arts, Lahore, and Textile Institute of Pakistan, Karachi. Her work incorporates weaving and textile design, and appropriates iconic images from both Western and Pakistani art and culture to address social and political issues, both locally in Pakistan and globally.

Emma Drew: For viewers, and coming from someone with a fairly limited knowledge of Pakistani history and politics, how much cultural context do you think is necessary for engaging with your work? What would you like to communicate to the uninitiated? How is that different for the informed viewer?

Imrana Tanveer: My work is mostly political and I use the language of satire and wit to address issues, which can be relatable and understandable to both informed viewers and viewers with limited exposure to Pakistan. I believe one cannot get rid of or deny fatal realities of our surroundings; what I see and what is happening around me is reflected in my work. The work of art and its interpretation is subjective. Reading a visual work cannot be divorced from its content, context, and concept; sometimes this meaning is different from the meaning that the artwork really has. For instance, works of art with particular ’titles’ are interpreted in that frame of context, while a work titled “untitled” gives more freedom to think in multifold contexts. (However, I don't like works with no titles—it's like one gives birth to a baby and doesn't name him/her). Therefore, the hardest part of my practice is coming up with titles which best reflect the work visually and conceptually. Sometimes it takes a lot of effort and time to title a work, compared to the execution process.

ED: What are your artistic origins? What would you say are some of your important influences (visual and otherwise; for example, I'm thinking of Kahlil Gibran's “Scarecrow” passage you quote)? Did your practice begin with a desire to explore the political, social, etc., or did that develop later on?

IT: I was never an artist; never had I thought something of the sort. My father was very strict about studies; I remembered once he slapped me for not filling the right colors in a cockroach drawing. (To tell you the truth I hate cockroaches and at that time I never understood why they have so many legs and why the school and the publisher of the drawing books chose cockroaches among all the creatures for coloring). I used to draw the homes of my neighbors while sitting on my rooftop. I colored the drawing books and painted landscapes. But all that was just a leisure activity and my father always wanted me to be a doctor so he never thought of polishing my artistic instincts, nor was it entertained in the conservative social and familial structure of our country.

I graduated from the Textile Institute of Pakistan, Karachi as a textile designer in 2008 and started working in the denim industry. Working there I realized that I am not the kind of designer who just sits in a studio and makes (copies) readymade designs. I wanted to draw and create designs of my own, but the market and industry didn't allow me. A lot of my inspiration and appreciation of art developed during my undergraduate studies, when Sumbul Khan and Rizwanullah Khan were appointed as our Art History teachers. After a year and a half working in the industry, I quit my job and one of my dearest friends suggested I join the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore. I joined the Master program in Visual Arts in 2010. Those two years were crucial, as well as helpful in developing and polishing the artist in me. It was hard to understand and learn in an art school as compared to having a background in design, but eventually I learned how to amalgamate design and art to the point where it speaks out loudly.

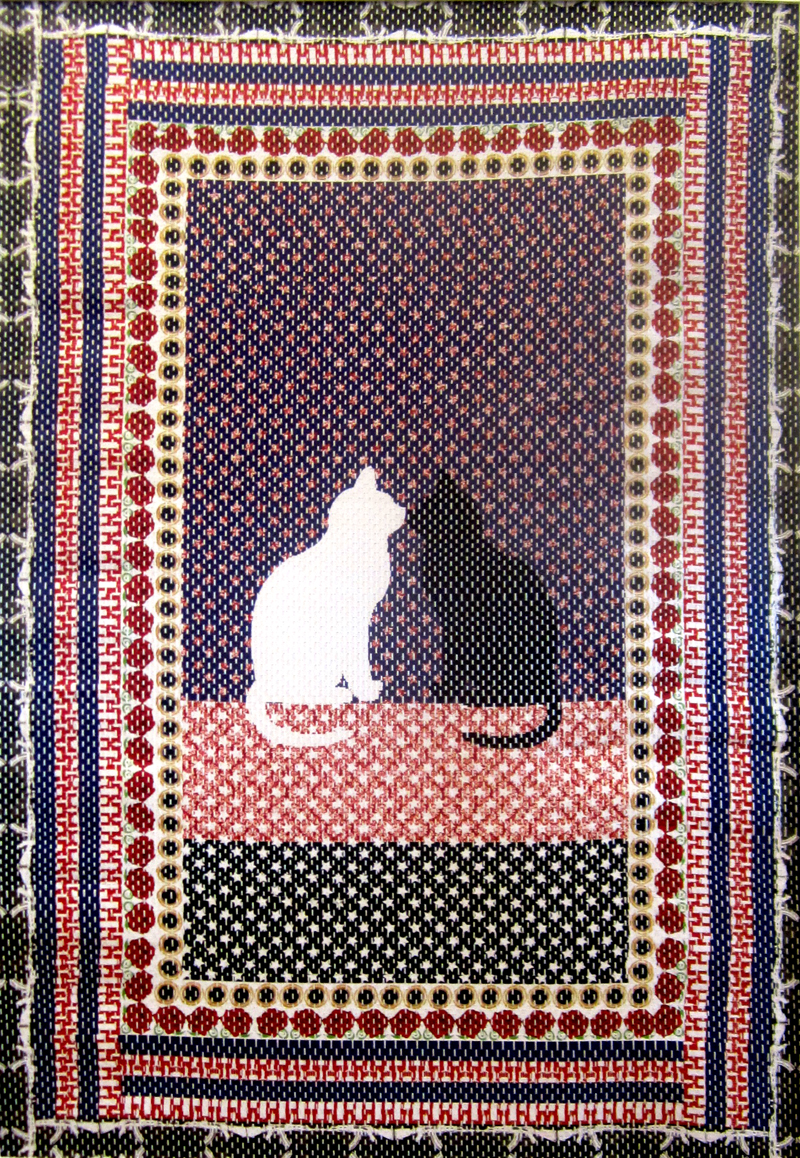

Today, the role of social media is very important. I too spend a lot of my time on the social media websites, my most immediate influences and inspirations come from these platforms. Apart from that, a lot of readings during my studies helped shape my ideas and concerns on a local and global level. The writings of Franz Kafka, Khalil Gibran, George Orwell, Orhan Pamuk, and Nizar Qabbani influenced me. My works often have images of animals, e.g. Black Cat White Cat, imagining a world ruled by animals, referring to Orwell's Animal Farm (in fact, animals are better at ruling than humans; at least they keep system of justice in balance). I love the idea of metaphors, repetitions, and patterns. And I like to portray core ideas using visual language in disguised yet apparent ways. My work is shaped by the happenings of my immediate surroundings. Therefore, the socio-political concerns have been there since the beginning of my practice and are still developing and molding in reference to global scenarios.

ED: How do your materials and medium choices work with the content of your work? What formal elements do you feel are most expressive, or necessary, for you? I'd be interested to know how the use of rivets, holes, shadows and mirrors (Post Betrayal and Love Affair, for example) came to be and why you find them useful or fruitful. Are there other mediums you're hoping to work with in the future?

IT: My proper practice started during my thesis time. I wandered around old Lahore and found plenty of textile materials, all of a sudden it started making sense to me. At first, I would buy different fabrics and textile materials, later I thought of creating work out of it. Sometimes the medium dictates what I do and sometimes it's vice versa. The tactile quality of the textiles and the use of bold and primary colors are my formal concerns; it gives me much freedom of exploration and expression. One of my post-grad jurors once told me, with great foresight, “You must learn and know when your material becomes your medium.” And it didn't take me long to understand what this meant.

The work “Post Betrayal” was an installation canopy from my thesis work, which evolved and formed after I purchased the camouflage fabric. The market from which I bought the fabric used it to make canopies for shelter from the sun and to cover goods on trucks in bad weather conditions during transportation. The parachute camouflage is also used for tents. I wanted to use that canopy and the process of punching holes by overdoing and repeating the process of punching rivets numerous times: thousands of small metallic rivets punched on camouflage tent representing bullet holes. The purpose of the tent is to protect and provide shelter and the rivet is used to strengthen it, but by overdoing the punching, it represents our own behavior and attitude towards the safety of the state and borders.

Right now I am focusing on weaving, it is a very vast medium in terms of exploration and experimentation. The idea of creating works through weaving compliments and coheres the contextual and conceptual dialogue of my work. It interrogates and enlightens the world we develop and live in by constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing it again and again. I also draw and paint occasionally but it’s a personal expression. I don't exhibit this, but perhaps I will in the future.

How do you think religious, national, and pop iconography, all present in your work, inform our conceptions of identity, religious, national, or other? What draws you to include them in your practice?

Because I live with all these. From political talks to bizarre events and from wall chalking or the bombardment of advertisements and the breaking news of any religious, national, or political content––it all affects me and my work practice. I like working with and incorporating metaphors and patterns, and my work varies with the change in current of socio-political scenarios. The “impact” of these events forces me to include such iconography in my practice because these icons are relevant and universal and somehow understandable by wider audiences.

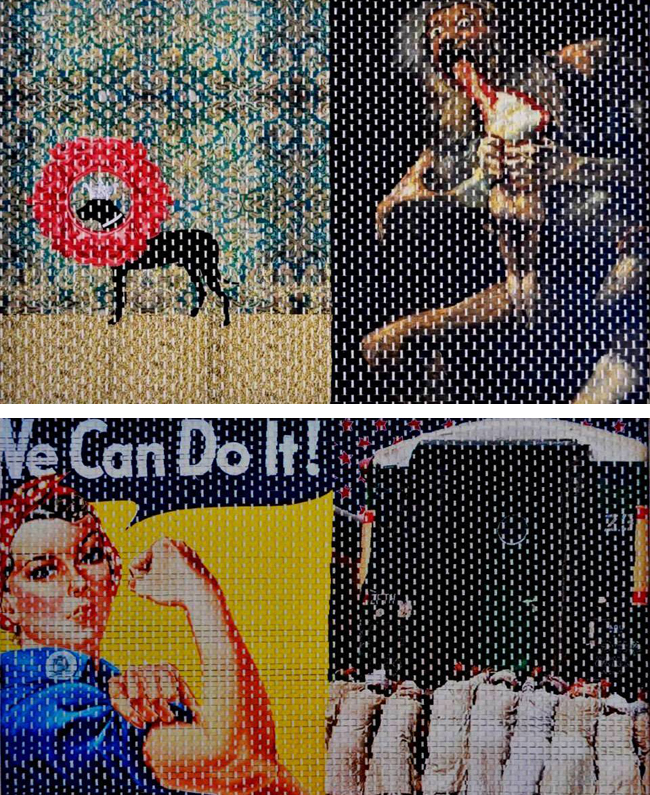

ED: Is there a specific relationship you feel you and your work have with Western art (history)? Does that matter for you specifically as a Pakistani, non-Western artist? From Warhol to Goya to Rosie the Riveter and from Mazor chador to Islam to Pakistani history, what role does tradition play in your art?

IT: I started incorporating Western Art and iconography in 2013 when I started teaching art history to second year students at the Textile Institute of Pakistan, Karachi. One of the biggest challenges I faced was that students were not able to relate to Western paintings and ideas. So, I started explaining those paintings and visuals to them by plotting it in a local context. And I found there is a lot more to Western or Eastern Art History. Other than the historical context, the generalized idea of a visual can be relatable to anyone. I mean the concept of Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son was always a matter of great interest and irony since ancient times. One can still witness the many sons devoured in the name of terrorism and wars. Similarly when I first saw a Rosie the Riveter poster my immediate response was “Oh really.” Later, I produced a work titled the same, but in contrast to the Riveter, it is an image of men pushing a local train's bogie (as apparently it was low on fuel and the Railway Industry had fallen to bits because of corruption).

The role of tradition is very important as I use traditional textile techniques, i.e. weaving. However, I incorporated and amalgamated it with fine arts and it became my medium of expression. This is the case with Mazar chador and Pakistani history.

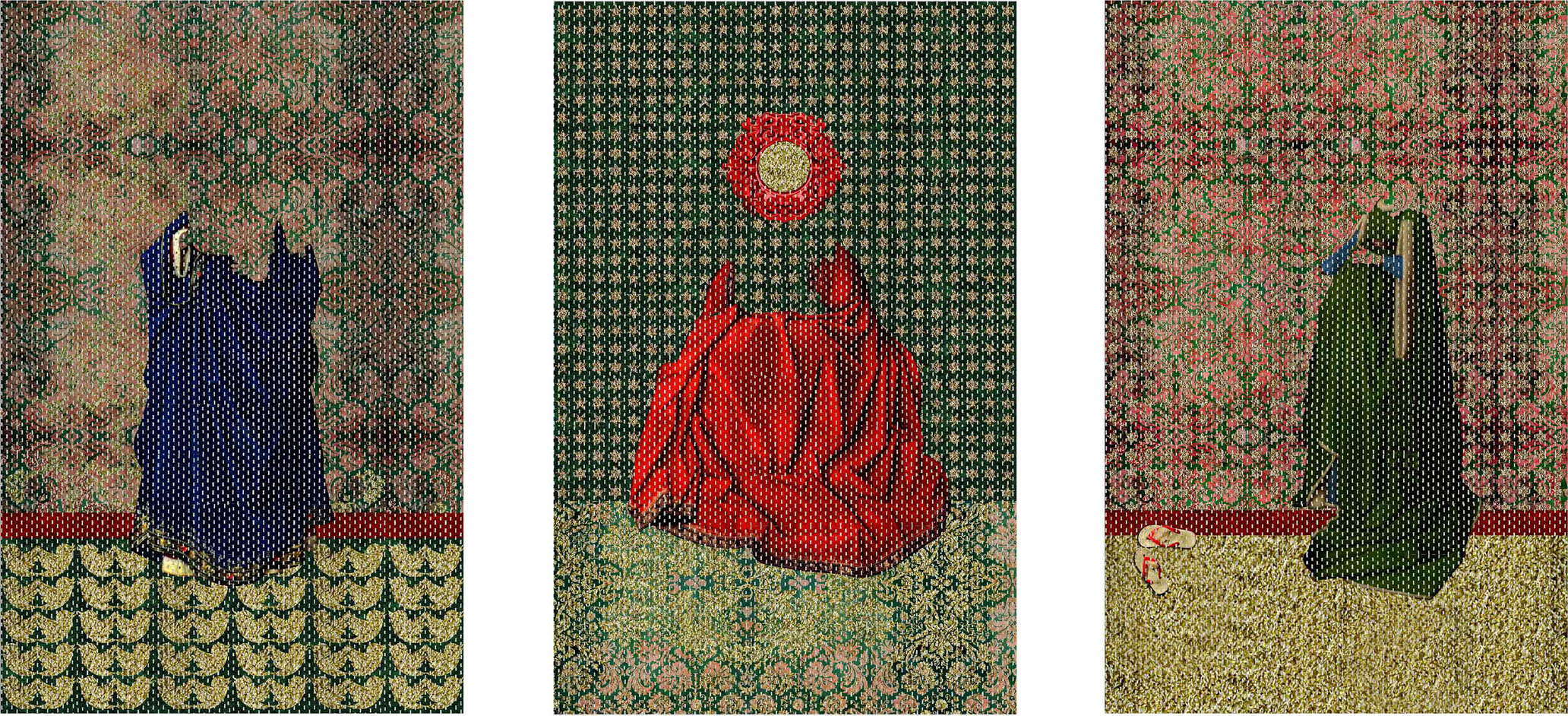

ED: The triptych [title image', Our Lady In Saturation,] is so sumptuous and haunting and the rendering of the texture and weight of the dresses in textile is really impressive. Adoration of Yellow Duckling has a nice level of absurdity or irreverence--and obviously there are some common motifs from previous works (the sunglasses, empty frames). Can you tell me a little more about these pieces? They both resonate with other works of yours but feel different in tone and execution. Absence seems key across the board...

IT: The Triptych [title image] is inspired from three different paintings of 15th century famous Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck: The Lucca Madonna, Virgin and Child, with Saints and Donor, and Arnolfini Wedding Portrait. I wanted to work with the subjects, things, materials, and preferably clothes without any bodies, in order to investigate the ideas in a new context, i.e., how we stereotype or generalize things on the basis of who is wearing what. It's no wonder textiles have always played a vital role in history of mankind and have been the symbol of status, but when we show these textiles and clothes without the wearer it changes the meaning entirely. So the triptych work investigates the role of women in many forms. I am always surprised and haunted by the idea of how people label women in particular; I am not speaking specifically as a feminist, but rather about the behavior of judging or having assumptions about other people. Take the Virgin Mary, she was pious yet accused by her own people, or Sita (Hindu Goddess) who was accused, abducted, and exiled while her husband was away.

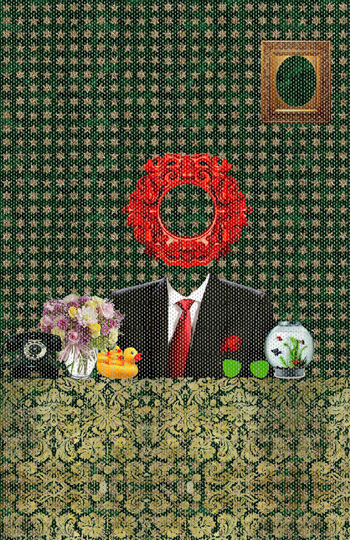

I used to play Hoyle Board Games on my computer. It has a customizable character. You play and win coins and use those coins to buy different decoration items to accessorize your portrait and background. It’s like the player is simply sitting, and in the background or on the table the player has the room to decorate. Whenever I was losing the game, or not interested in playing anymore, I bought vases and paintings and lights to decorate my profile. It's like a free-time activity for killing boredom. This idea really inspired me to work on Adoration of Yellow Duckling––the image of the head of the state who is sitting behind his office desk (I deliberately omit the face to relate it to everyone or anyone). It was quite ironic that most of us don't even know who our president is and he is just there to fill the chair and is perhaps killing time. As you yourself well concluded, “Absence seems key across the board...”

ED: What kind of reception has your work received? I'd imagine it's been pretty varied—thinking again of Post Betrayal at the residence of the American Ambassador—depending on the audience and exhibition venue.

IT: Yes, you are right, my work receives varied reception. But to tell you the truth, it wasn't the American Ambassador who minded displaying such work or registered any kind of offense, but rather my own people. I remember, on the day my thesis show opened, the curator of the gallery made all her efforts to not let visitors see my work and when the people from the American Council General visited the gallery, she sent her assistants to pull off my work Tashakur (Thanks) from display, which I obviously didn't permit. They really welcomed criticism and were friendly to talk about my work and art practice. Other than that, my solo exhibition titled “I Saw Two Crows Building a Nest Under His Hat” was considered the one of the Top 10 exhibitions of 2013 in line with Monir Farmanfarmanian, Reza Derakshani, Rana Begum, and Maimouna Guerresi to name a few.

Could you talk a little more explicitly about the political and social landscape in Pakistan (or Karachi in particular) that your work engages with and interrogates? How are these realties and issues manifested in your work (or, which specific symbols or icons express best the topics you're interested in or the situation as you see it)?

IT: In politics nothing is predictable at all. The Army coup of 1999 led by Chief of Army Staff Musharraf, overthrew Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, announced a State of Emergency in Pakistan, and then sent Sharif to exile to Saudi Arabia. And in 2013 the current prime minister Nawaz Sharif came back with a bang, got elected, and put Musharraf on trial –a literal example of "Games of Thrones..." Pakistan's social, cultural, and political landscape changes and varies too fast. We are a nation of very emotional and sensitive people. There is a lack of tolerance among people. A flood can unite us or a small quarrel can lead to bloodshed and violence. The country is going through a series of chronic and dreadful problems of political, social, and economic nature, but yet we survive in hopes of Hope.

Use of animal forms, patterns, and golden roundels are a few of the symbols common in my work. Other than symbols and imagery, the idea of blurring the imagery by weaving is my form of expression. My medium and process of creating and executing the final piece are equally important, too. It interrogates and enlightens the world we develop and live in by constructing, deconstructing and reconstructing it, i.e. through the transmutations in form of the weaves. And all of these find their way towards policies, politics, and culture in a witty, slapstick and satirical format.

ED: Thinking in part about the mission of Emergent Art Space--to connect students and artists across cultures--and your interest in cultural identity amidst the global, how do you think your work (and maybe contemporary art in general) addresses or interacts with our ever-expanding sphere of knowledge, experience, and exchange (or, globalization, for lack of a better word)?

IT: First of all I congratulate EAS for such a lovely and great initiative, and for providing a platform where students, artists, professionals, teachers and anyone can share his/her knowledge alike. The world has shrunken to the point that there are no boundaries anymore and social media is a great platform to promote and share works with wider audiences in general. There were times when an artist had to look for the galleries; now they have the choice of uploading and showcasing works online as well. You upload something and it spreads virally, which expands knowledge and experience in one way or another.

ED: As always, what's next for you?

IT: Next is the path with many milestones to achieve. I'm in a state of organizing chaos. I am working towards my exhibitions at home and abroad. Soon I will be presenting my work and a talk at the Islamabad Literary Festival ILF (curated by Lavinia Fillippi, an art historian/curator from Italy) at My Art World Gallery at the end of April. Other than that I'm working for an exhibition in Dubai where my work got selected among Golden Winners category.

ED: How has teaching and writing changed your own practice as an artist and your interaction with the art world? Do you have different goals you're trying to accomplish as a teacher, as a writer, and as an artist?

IT: Teaching helps me to learn more about history and to contextualize my work. Writing on the other hand is very poetic and more occasional; I write when I feel like writing or I feel it reveals something to me. I always write a paper about my exhibitions to articulate my work. I am more focused in my art practice, sacred about writing, and honest about teaching. And all three are coherent.

View Imrana Tanveer's EAS profile here.