Interview: Yunjin La-mei Woo | Seoul, South Korea

Yunjin La-mei Woo is a performer, street artist and ethnographer based in Bloomington, IN, USA. Her research interests range from ‘life’ as a sociohistorically defined condition to political art and critical studies of everyday life. In particular, Woo is interested in virality and parasitism as metaphors and how they can be used in art as a ‘counter-performance’ to the dominant narrative of ‘life.’ Her performance and “para-sitic” practices have been hijacking various systems and modes of conduct throughout South Korea, China, the United States, and Germany. Woo holds an MFA from Seoul National University and is currently a PhD student in Communication and Culture at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Where did you grow up and where do you live currently?

I grew up in Seoul and spent the majority of my life there. I just noticed I used 'there' instead of 'here'—something again reminds me that now I live somewhere else. Since I moved to Shanghai in 2011 and then to Bloomington (US) for my doctoral study the following year, I've been a "nonresident alien." It's an interesting legal definition and cultural idea to think about. I'm glad its liminal and marginalized conditions have helped me understand things I didn't see before or grasp them more palpably.

Can you explain a little more about how your understanding of the world was shaped by being placed in a liminal position?

In any society, I think there are liminal identities, positions, or states people find themselves in, and I've been in such positions both before and after living "elsewhere." In many different senses of the term, I believe one can be belong to elsewhere either voluntarily or not. But, part of how moving to new places as an "alien" has helped me is that it has raised my awareness of what it means to be in such states in larger contexts. For instance, the processes of being legally categorized, documented, and treated as a foreign element in a supposedly self-contained society forced me to think about the reasoning behind how certain bodies are perceived in particular ways. It has also been interesting to see how my perceived ethnic identities have shifted from 'Korean' to 'Chinese' (as I looked Chinese in Shanghai until I spoke), and then to ambiguous 'Asian' or sometimes 'Asian American' in the US due to my American accent. Being both a PhD student and a university instructor simultaneously, as well as changing my major from Sculpture to Cultural Studies, have also been 'in-between' experiences. I often find myself neither 'here' or 'there,' while at the same time being in both.

What inspires me isn't unrelated to this idea of 'alien' either. I study contagion as an experience of losing oneself, both literally and figuratively. In contagion, subjects pass into each other and gain proximity genetically, affectively, and morally. In a sense, it's a process in which the boundary between 'native' and 'alien' becomes infected and contaminated, in a critical sense. This binary opposition can also be iterated in different but related binaries: self and other, internal and external, normal and abnormal, healthy and ill, clean and dirty, or safe and dangerous.

Does this idea of contagion come into play with your Centipedes piece? How and on what level?

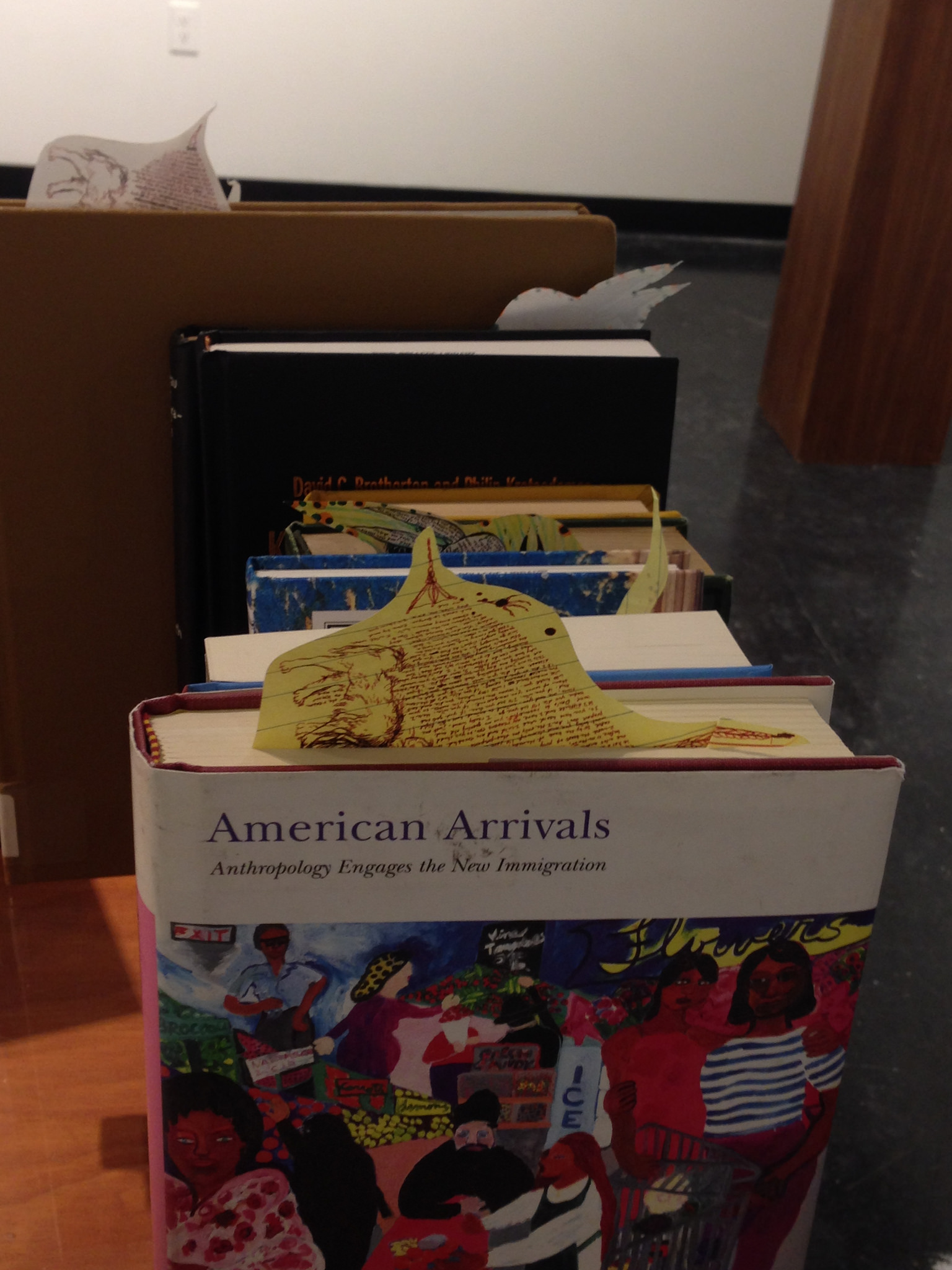

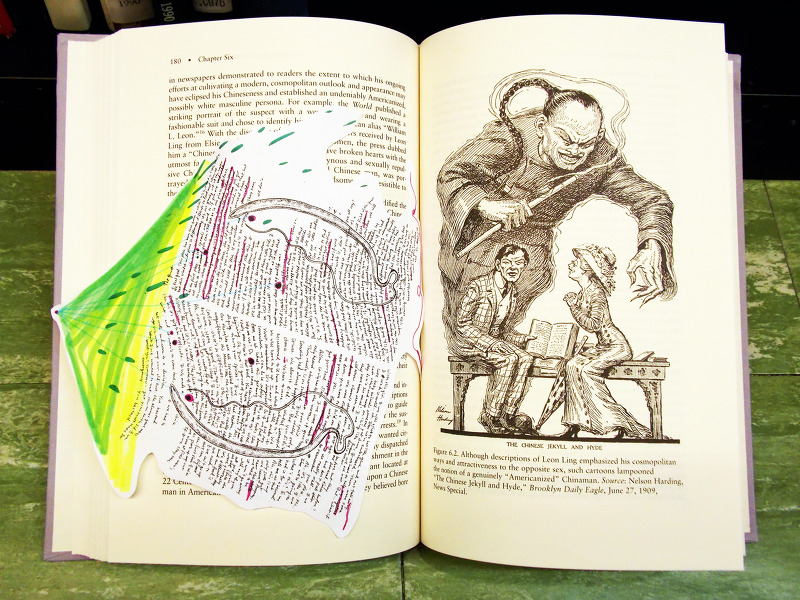

I see the Centipedes as infectious vectors, or 'bugs' in its figurative sense, that crawl into cracks and crevices. Like someone's private notes we sometimes find in second-hand books, my little prints borrow others' space and secretly occupy library systems. They are foreign bodies to the books that they occupy. Since the prints are inserted into books that have resonating themes such as immigration or foreign policy, they are meant to 'contaminate' the narratives in the books on the content as well.

Where did you go to school and what area of study did you focus on?

From early on, I thought I'd do something related to art but not in terms of a specific occupation like artist or art teacher. It's strange to explain the thought I had as a kid, but I somehow always had this kind of ambiguous idea. Now I study and teach cultural studies, write, make art project, and curate exhibitions. I see this as my ambiguous, roundabout ways of 'doing something related to art' without a clear occupational position. In a sense, I'm an 'nonresident alien' in terms of disciplines, too. In the cultural studies field, I'm an artist who also researches and writes, but in the arts field, I'm an academic who also makes art.

I think this is wonderful. In my experience these kinds of intersections are vital in creating important conversations in the academic world and the art world.

I received my MFA in sculpture at Seoul National University, and I chose sculpture thinking that it would promise me the most leniency and 'promiscuity' in terms of disciplinary boundary breaking. It turned out to be about right. In a very broad sense, I think sculpture is a study of relations in human reality, either it be physical or social. I was lucky in that I got to learn a wide range of techniques and modes of thinking, from metal welding to performance art.

Can you tell me a little bit about how you composed the stories that are used in The Centipedes? What inspired them and what do these stories mean to you?

The Centipedes started from an actual, tiny centipede I encountered from a plant pot in my house. It was a very small one with red legs and a dark blue body. I was repotting the plant when the centipede came out of the soil, and I was half surprised and half mesmerized by it. Surprised because I didn't expect the plant pot from a large grocery chain would have a centipede inside, and mesmerized because it was quite beautiful actually.  It was like discovering 'wildness' inside a commodified, 'tamed' object and space. I like living with many plants in my place, and living entities give me the most inspiration including plants and other life forms live near them. I'm also interested in myths or narratives that imagine more fluid exchanges or relations between entities, like portraying objects as living beings or non-human entities as intelligent aliens with different languages. So, I started writing short stories that are loosely connected to each other by some mention of centipedes in different bodies and minds, alluding to Korean folktales where centipedes have the ability to change their appearances at will.

It was like discovering 'wildness' inside a commodified, 'tamed' object and space. I like living with many plants in my place, and living entities give me the most inspiration including plants and other life forms live near them. I'm also interested in myths or narratives that imagine more fluid exchanges or relations between entities, like portraying objects as living beings or non-human entities as intelligent aliens with different languages. So, I started writing short stories that are loosely connected to each other by some mention of centipedes in different bodies and minds, alluding to Korean folktales where centipedes have the ability to change their appearances at will.

It was like discovering 'wildness' inside a commodified, 'tamed' object and space. I like living with many plants in my place, and living entities give me the most inspiration including plants and other life forms live near them. I'm also interested in myths or narratives that imagine more fluid exchanges or relations between entities, like portraying objects as living beings or non-human entities as intelligent aliens with different languages. So, I started writing short stories that are loosely connected to each other by some mention of centipedes in different bodies and minds, alluding to Korean folktales where centipedes have the ability to change their appearances at will.

It was like discovering 'wildness' inside a commodified, 'tamed' object and space. I like living with many plants in my place, and living entities give me the most inspiration including plants and other life forms live near them. I'm also interested in myths or narratives that imagine more fluid exchanges or relations between entities, like portraying objects as living beings or non-human entities as intelligent aliens with different languages. So, I started writing short stories that are loosely connected to each other by some mention of centipedes in different bodies and minds, alluding to Korean folktales where centipedes have the ability to change their appearances at will.What was your experience in watching people interact with your piece? Were you able to hide the centipedes in working libraries and observe their reception as they were discovered by strangers? How did the effect of the piece differ based on the setting? For example, between an art gallery, and a library.

I never tried to hide and watch people interacting with them. Although I thought about the possibility of it, I found it was more appealing to leave them to take their own courses without knowing exactly what happened to them. I wanted it to be a kind of mystery to me, like how some organisms leave their eggs after laying them in an appropriate environment. For the same reason, I didn't leave any information for people who would discover them to track down what the prints are for or made by whom. I do keep an inventory of where they are first 'laid' so that I can go check if I want though. I've never visited them yet, however.

How was the experience of having another person translate your stories into English? What were the challenges or surprises?

About the translation process, it was quite interesting. I could've just written the stories in English, but at the time, it was important for me to have another person translating my "original" work as a creative process on its own. Now I have come to think of translating one's own work as a creative process, too. It started from the idea that the ethnographer is a cultural translator of the culture that she studies and represents in her writing, which assumes culture as a text, especially an unwritten text that needs to be discovered, written, archived, and hence "saved." In this model, the ethnographer is also the author of the written text once it is written, while the people who practice and embody the culture become mere informants without given enough credit or authority over how to understand the meaning of their modes of living. I wanted to challenge such assumptions by putting myself into a position where I have to negotiate the meaning of my stories with someone else with different sociolinguistic and cultural assumptions.  It was challenging because the ways in which our roles constantly changed between ethnographer and informant, author and translator, or artist and participant. As our roles shifted, so did power relations. For instance, it was challenging for me to decide to what degree the English translations should be different stories in their own right, while it might have been challenging for the translator to not see my position as the author of the "original" stories as somewhat oppressive rather than negotiable or contestable.

It was challenging because the ways in which our roles constantly changed between ethnographer and informant, author and translator, or artist and participant. As our roles shifted, so did power relations. For instance, it was challenging for me to decide to what degree the English translations should be different stories in their own right, while it might have been challenging for the translator to not see my position as the author of the "original" stories as somewhat oppressive rather than negotiable or contestable.

It was challenging because the ways in which our roles constantly changed between ethnographer and informant, author and translator, or artist and participant. As our roles shifted, so did power relations. For instance, it was challenging for me to decide to what degree the English translations should be different stories in their own right, while it might have been challenging for the translator to not see my position as the author of the "original" stories as somewhat oppressive rather than negotiable or contestable.

It was challenging because the ways in which our roles constantly changed between ethnographer and informant, author and translator, or artist and participant. As our roles shifted, so did power relations. For instance, it was challenging for me to decide to what degree the English translations should be different stories in their own right, while it might have been challenging for the translator to not see my position as the author of the "original" stories as somewhat oppressive rather than negotiable or contestable.It’s amazing how much power lies in the person who is wielding language. At the end of this process, did you feel as if anything valuable was lost or compromised when your original text was translated?

I see the translated versions more as different pieces than my original text converted into another language. I worked with an amateur translator/writer, Mathew Bumbalough, who lived and worked in South Korea for seven years. My idea was that his lived experiences and lack of formal training in translation would leave more room for him to write his own stories in the process. I originally wanted to hire two more translators who would translate his English translations back to Korean and then to English again without access to my original version. Unfortunately, it wasn't financially plausible. Given the opportunity, it would be great to see how the stories would turn out if translated by a professional translator as well.