Teaching art to kids in a remote Indian village

Kolkata artist Pallavi Das shares here her experience teaching art to young students at the Manjushri Public School, in the Indian state of Sikkim. Rather than following the traditional art history curriculum, she wanted to create a 'free space' where the kids could participate and freely interact with the artists of the past, with Indian folk art as well as with iconic Western works.

Paola Loomis, in San Francisco, joins in with some questions.

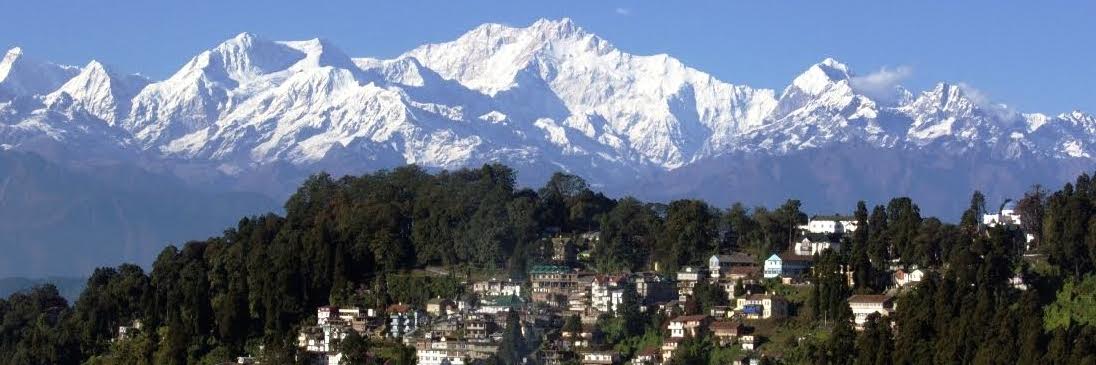

Sikkim is a small Indian state surrounded by the Himalayan range, and bordered by Nepal, China, Bhutan, and the state of West Bengal. It is considered to be the last to give up its monarchy and integrated to India in 1975.

A residential school, the Manjushri Public School was founded in a small valley called Temi Tarku. This school pushed the border of the standard educational system to create an alternative space, far from the urban society. Being in a valley, surrounded by hills, it was almost an isolated place. Communication with the world around was quite difficult. Newspapers and the internet could be accessed only once a while. Because of this limited accessibility to the media, the school focused more on the faculty and the students physical relationship with the world. It replaced the use of electronic media with reading books, gardening, learning music, and performance art.

A residential school, the Manjushri Public School was founded in a small valley called Temi Tarku. This school pushed the border of the standard educational system to create an alternative space, far from the urban society. Being in a valley, surrounded by hills, it was almost an isolated place. Communication with the world around was quite difficult. Newspapers and the internet could be accessed only once a while. Because of this limited accessibility to the media, the school focused more on the faculty and the students physical relationship with the world. It replaced the use of electronic media with reading books, gardening, learning music, and performance art.

Each and every student was responsible for cleaning and organizing the school compound and the surroundings. Here I was asked to participate in the school mission to restructure the pedagogy of the visual arts.

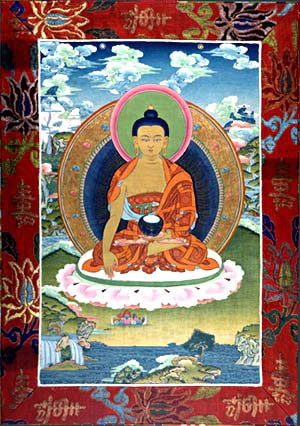

In this remote location, visual art was only known through the traditional religious Buddhist painting called 'Thangka'. My objective was to introduce some of the norms and forms of world art which I found is neglected in the Indian school education system. My challenge was not only to inform the students about both the world and Indian art history,and but also to let them physically absorb the varieties of style, and to understand history through a playful manipulation of famous artworks. I chose not to follow the chronology of art history but to start instead with the students’ own visual knowledge.

In my first class, with junior students, I started with prehistoric art as the first discovery of visual art. Informing them about Bhimbedka cave and Altamira cave paintings, I explained the use of colors in prehistory and the different assumptions behind creating those. Then I asked them to freely choose a subject they liked and paint it on different surfaces (paper, cardboard, stones).

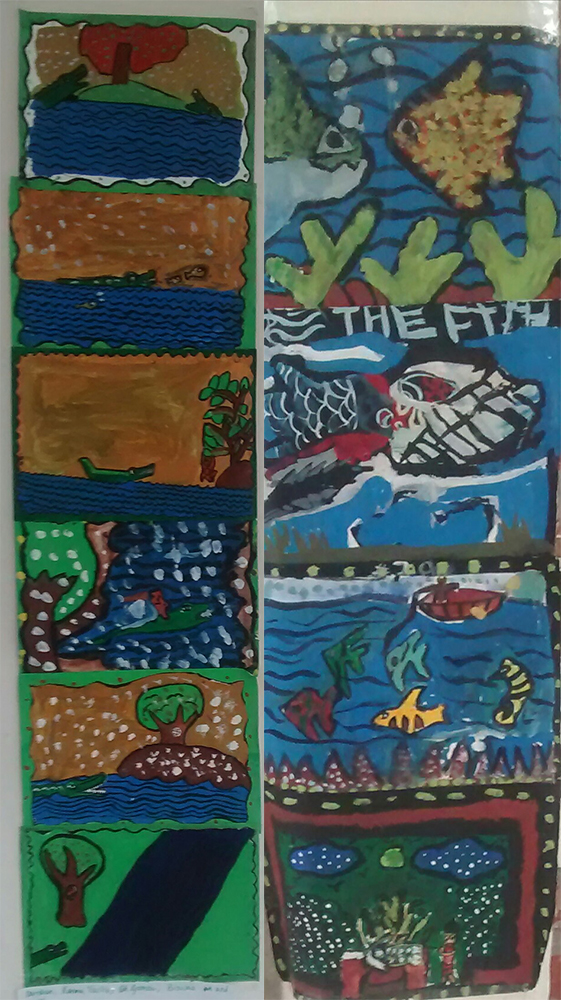

After mingling up with the middle grade students, I observed that they were familiar with visual narratives of comic strips. I came up with the idea of introducing them to “Patachitra”, the traditional visual narratives of rural Bengal. "Patachitra" are scroll paintings which visually narrate religious epic story. Interestingly, the rural artisans perform each story by singing out loud and revealing each scene by scrolling down the pat. These paintings traditionally use bright vibrant colors and bold black outlines.

I shared with them the history of "Patachitra", and then invite them to sit in a group and think of a story. Some of the group members had to plan and write the story plot, and some had to start painting each scene, using bright vibrant color and outlining them with bold black outline. At last they were asked to narrate their stories visually scrolling down each scene and vocally narrating their stories keeping the same essence of patachitra.

If texts are part of the work, is it possible to read some of the stories they wrote?

In the tradition of “Patachitra”, texts are not part of this art form. Rather than texts, they are closer to the performances. In the traditional style, the Patuas (the artists of Patachitra) paint the entire narrative on the scrolls and then roll them up. Then they compose the narrative in the form of a folk ballad, a poem, or just a story. When they gather their viewers they sang, recite, or just tell the story while unveiling the scroll scene after scene. You can call it the predecessor folk format of modern day film.

So, I'm afraid that there is no text or script. The artists have to perform the story orally as they unveil their Patachitra (scroll with paintings) scene by scene. It is a performance that go along with the visual.

to be continued...Stay tuned for the next episode!

Pallavi Das from Emergent Art Space on Vimeo.