Interview: Pebofatso Mokoena | Johannesburg, South Africa

South African artist Pebofatso Mokoena, living and working in Johannesburg, South Africa, is here interviewed by Uji Venkat, an Indian artist living in the Bay Area, California. He discusses his work and his influences, and addresses issues of African identity, stereotypes, and what it means to be an artist who wants to communicate cross culturally.

When did you first realize that you could speak to an audience through your art?

I remember when I was in a Human and Social Sciences class, in high school. We were listening to Bob Marley. I realized that Mr. Marley spoke in metaphors and allusion, totally different from the krump music I was listening to at the time. I could really feel the fervor that he sang with. That’s when I really became interested in another form of speaking, another way of presenting my opinions - as I wasn't a confident speaker back then. I became interested in poetry, and I started to write my own (seriously romantic) poetry for the ladies, but after a while, I realized that visual art was the best form to express my growing opinions about the world to people. Speaking in images became too great of an art form to not perform.

You’ve spoken of how artists have influenced you. Who are the South African artists who inspired you?

One such example is Nicholas Hlobo. Nicholas is one of the first authentically South African artists that I studied in high school. There were many others, but I connected with Nicholas’ work immediately. There is a sense of urgency in his work. It is current. I did have the chance to see one of his works four years ago in Johannesburg. It was one massive sculpture, the entire length of the gallery. I enjoyed Nicholas’ work from the minute I saw it.

There is also William Kentridge. He says something about what it is like living in Johannesburg which I connect to. The longer I stayed in Johannesburg, the more I got interested in David Koloane and Marlene Dumas. David is just brilliant, how he is able to capture the energy and the frenetic nature of a space with just lines. It really grew my interest in drawing more than anything.

Patrick Kagiso Mautloa is yet another artist that influences me. Even talking to him you feel like he is growing you and teaching you and then you are inspired to contribute to the arts community. As I grow older my interest grows in my contemporaries, like Julie Mehretu, Neo Matloga, and Bogosi Sekhukhuni.

When did you start participating in curated exhibitions?

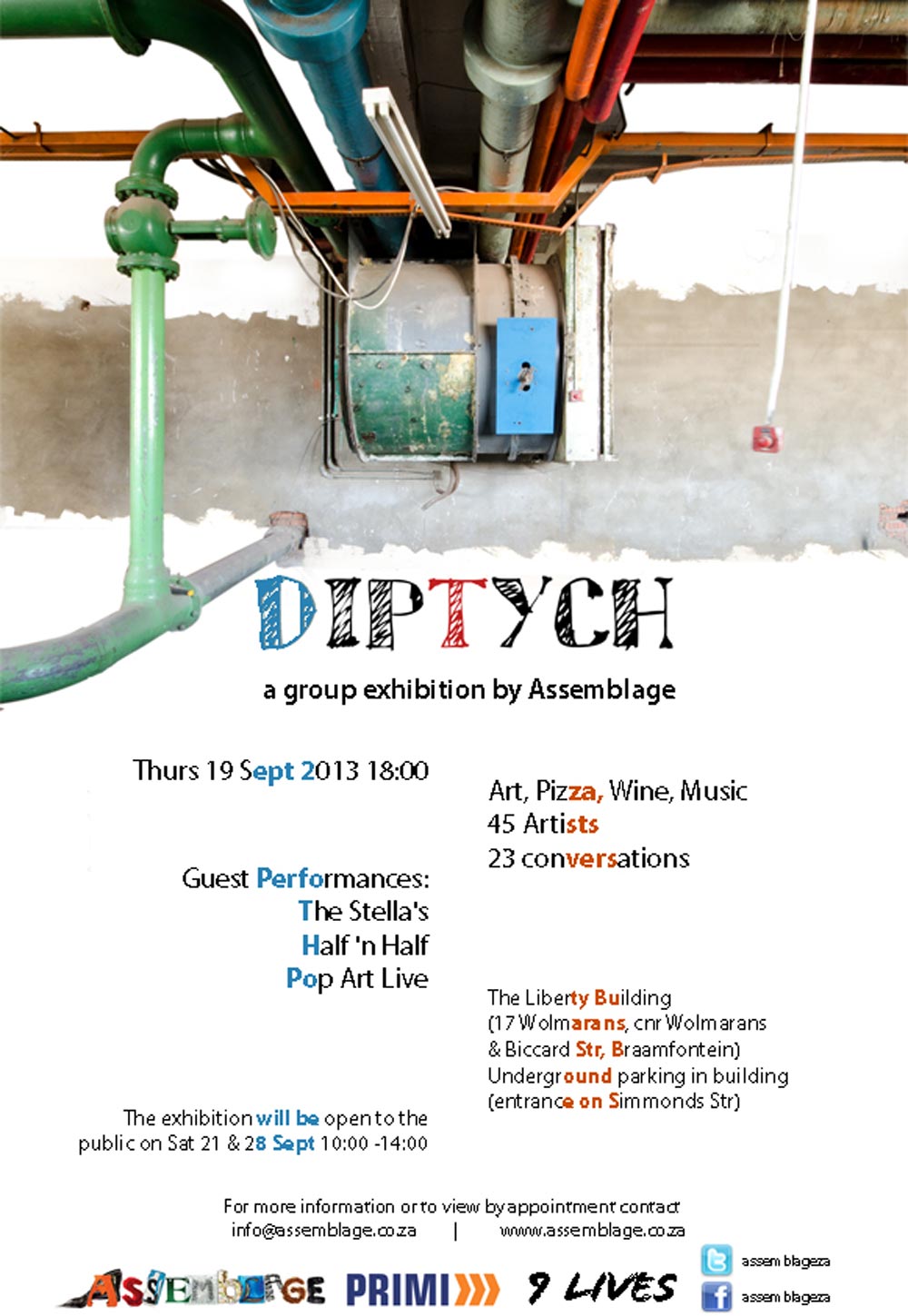

In varsity, while I was in second year (2014), I would work as an art student during the day - artist during the night. I would be printing my own drypoint plates during the nighttime, occasionally getting kicked out by security at the end of each night. It became fun after a while. Toward the end of my second year, I participated in a group exhibition titled Diptych and that exhibition made me realize that I really was participating in the art landscape.

Tell us about 'Diptych' and working with other artists.

'Diptych' was one of the first important shows for me because it showed me that there is more for artists after tertiary school. It is hard not to lose faith in the growth of art when your thoughts are streamlined in the school system.

Working with other artists felt great. There was a sharing of a common energy, more than ideas. That was primary. It was great to learn and great to experience. Especially because I am a lone artist, it was after I started working with other people that I realized that there are other avenues to push out your energy.

How much does your audience influence your work?

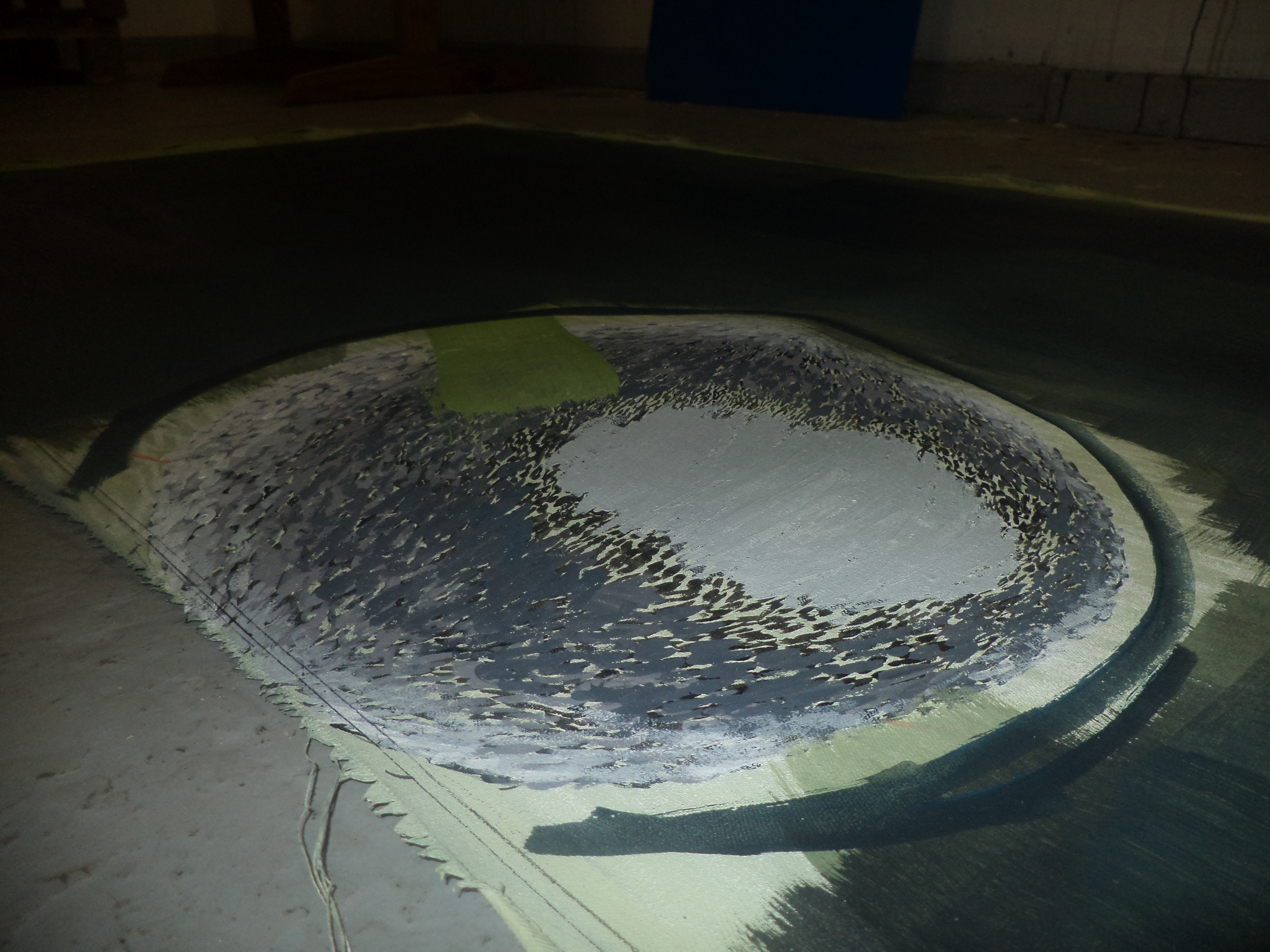

Context for me is very important: to be able to speak in a particular visual language to a particular audience, so that one’s work doesn't get ‘lost in translation’ in the spaces where the work is exhibited. I must concede, however, that my practice is a practice of the personal, through repetitive mark-making, along with a sensitivity to the material and the technique. As much as my audience influences my work, the more abstract verses of my work deal with personal strife. The audience reacts to my artworks in relation to their own experiences.

Do you like artist statements? I find that they strongly influence my experience of the artwork, as a viewer, for better or worse.

I’ve got a love-hate relationship with artists’ statements. Artist statements can become a kind of walking stick. They can take away from the overall experience of the work. But when I am confronted with a solo show, when the artist’s view is not in line with mine, I think a statement is helpful, and I think it is great to connect people to the work, so I enjoy reading the artists’ statements. Recognizable work is easier for people that are visually illiterate to connect with, but the minute your work is used as an allusion to something else, an artist statement is required to bridge the gap.

Tell us a little more about your process. Are there happy accidents?

They are a blessing and a curse. Experimentation, playing around, is a very important aspect of my practice because I think about lots of things at the same time. I put together things that are intrinsically connected in some way. The way I perceive life is a collage of everything that I see and feel. Then I just try to make a body of work that speaks to that.

If you think about it, we are all experimenting. Life is one big experiment. My interests are really quite expansive. You need the life of one thing to make another grow.You need the life of one thing to make another grow. Everything in life is connected. That is what I use in my art. Everything is connected and there are multiple life forms.

What is identity in the African context? And where you see technology coming in the picture?

I think the question of identity in an African context is a hotly debated question, because there will never be one African identity. Africa has 54 countries, meaning that there can never be one, holistic answer that encompasses everyone on the African continent - the continent is massive in its scope, geographically as well as historically - due to the sheer volumes of people, cultures, traditions, histories, colonialisms, political ideologies and so forth.

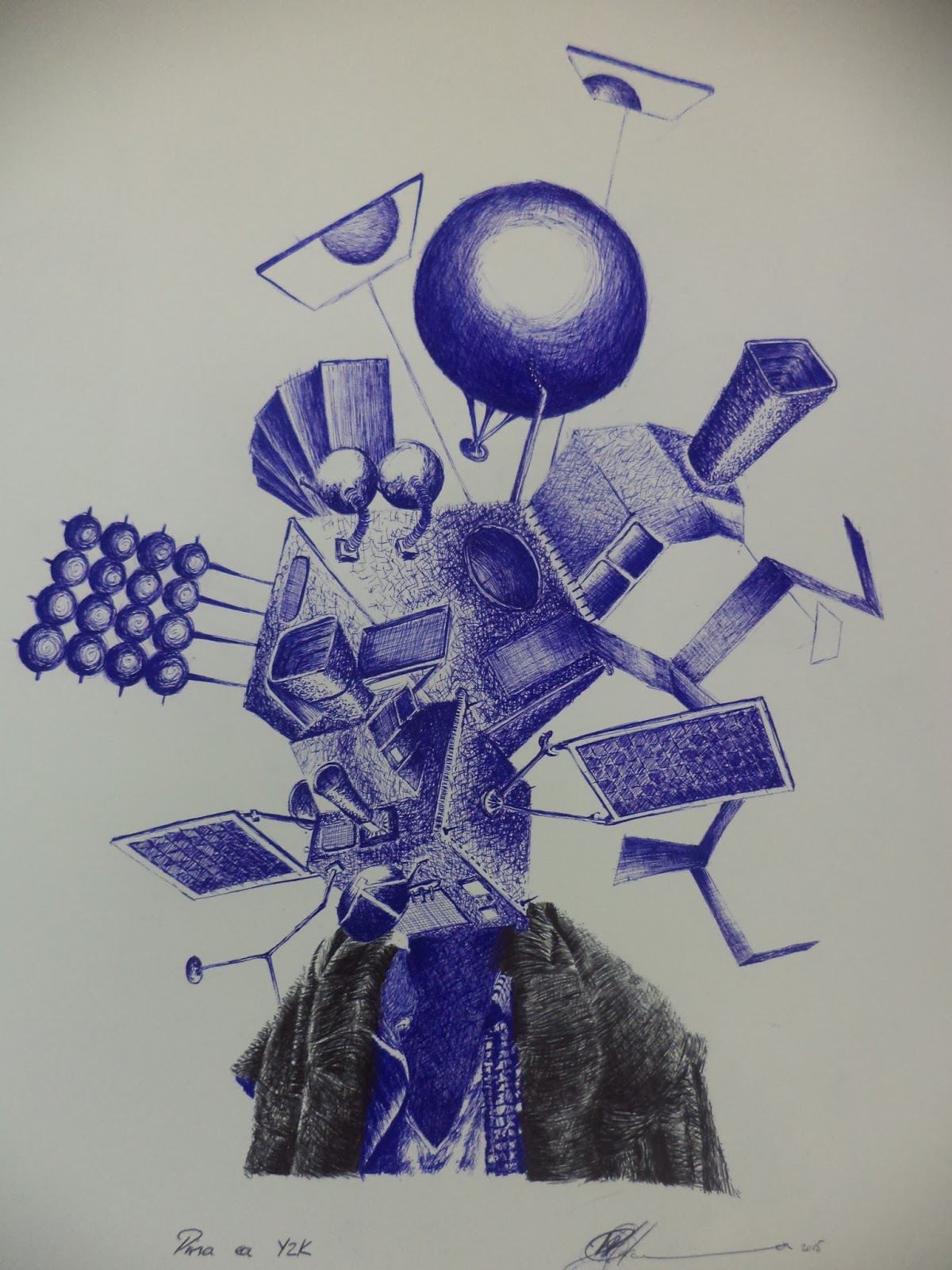

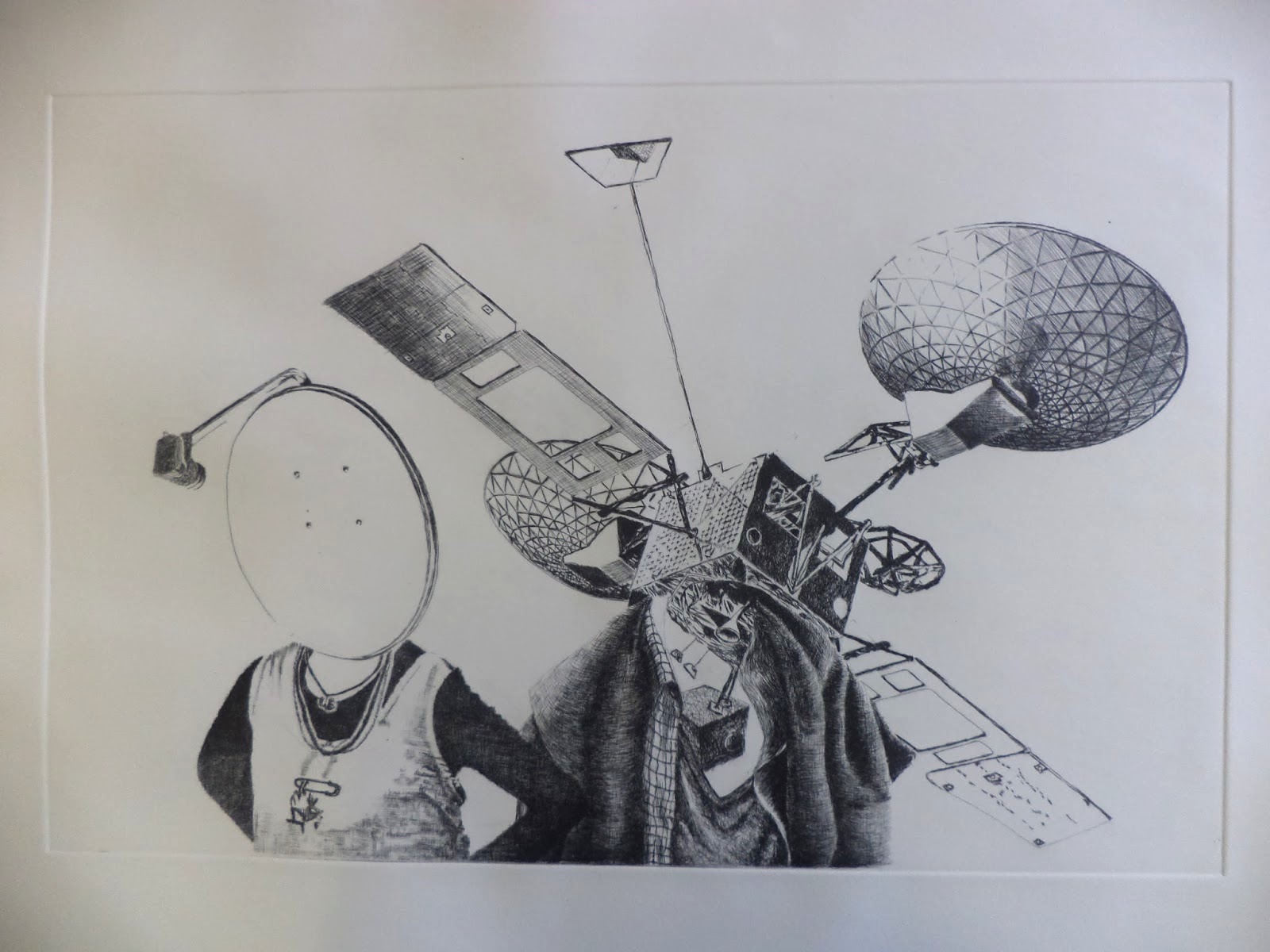

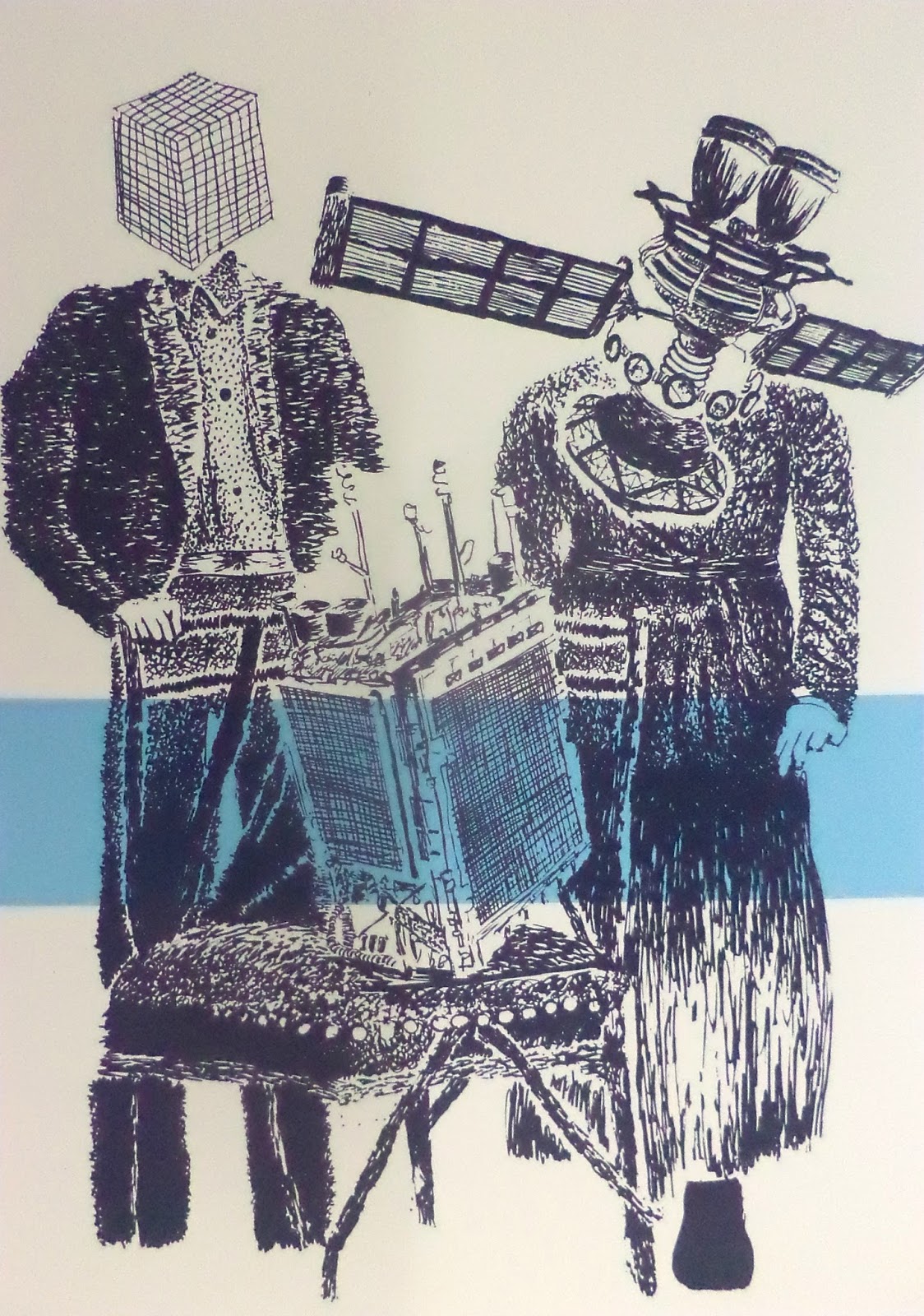

I really enjoy working on the metaphor that technology, specifically a satellite, can stand for a connection with memory. Satellites often herd communities of data, and in a sense, people are also communities of data collected through age and legacy. On the question of technology, there are many aspects in relation to global manufacturing, megafactories producing hundreds of thousands of electronics that find their way to Africa. The technological-transferring of imported equipment has an effect on the creation of locally produced electronics, which often changes the way in which people living on this continent may experience telecommunications/networks and their impact on their lives.

When talking about Africa, though, it is very important to denounce the interest in what I call ‘poverty-pornography’ that is fed out to the rest of the world, i.e. the pervading image that Africa is an uncultivated open-air veld*. It is important to visually break down the stereotypical ideology of ‘Africa, a place to scramble for.’ Cameras, for example, have a role to play in how groups outside the continent see this continent.

There are groundbreaking inventions, ideas being achieved. There are art practitioners, engineers, and even university students living and working on the continent who are working in technology fields and who are trying to redefine what technology means in the African continent and for Her people. We would be wise to pay attention to what they have to say.

You said, “I aim to tell stories about individuals searching for other humans to share our experiences and conversations of daily life globally…” Can you explain what you mean? By daily life globally, are you referring to cultural differences?

Somebody has referred to my silkscreens as “global”, which to a point excited me, because I managed to touch on matters that could be received and understood on any stage. The news have some interesting takes on stories they investigates; reading also helps to gain another perspective; talking to people about living in the world also gives me different perspectives.

Just a couple of days ago I saw someone knocked over in a car accident; yesterday, I almost got knocked by a car myself - it is these perspectives I try to incorporate in my work - create my own narratives, so to speak.

With a multilingual upbringing, I see the way I draw as a language. The way I speak is a language, spoken and written. The way I dress is a language that communicates something. It is what got me interested in being an artist. I could convey my message in multiple different ways to people that speak different languages. I could be more inclusive.

The silk screens were about how to break the generational gap. There is a lack of communication and connection. If we were to center the entire community around a common denominator, for example a cucumber farm, where everyone eats cucumbers (metaphorically speaking), who would do what is necessary to raise the cucumbers and keep the farm alive? A common interest binds people together. “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” is a Zulu phrase that translates into “A person is a person because of a people"

What direction would you like to expand your work into next?

I never wanted to make my work for other people, but there is a kindness to the people that understand my work. I send out positive energy and I get back positive energy from them. The more I work, the more I am able to see that there are people who are accepting of the energy in my work. At the end of the day they become friends and not collectors and curators.

In my current bodies of work, I am working with concepts of “space” and “peace.” I think about what I do as a healing project, fighting every action that we take against each other.

I’m moving more into abstract. A black artist has to navigate their art through literal space. If they veer into abstract, people don’t always buy into it. But abstraction is empowering, it allows me to counteract news after news of trauma. It is not necessarily in line with what I am “supposed” to do as a black artist. But we are making and building our own history. I am now part of the healing project. I draw peace.

*Veld: open, uncultivated country or grassland in southern Africa. It is conventionally classified by altitude into highveld, middleveld, and lowveld.

Pebofatso Mokoena, born in 1993, is currently a practicing artist at 'Assemblage' in Johannesburg. He has participated in a number of curated exhibitions including Inner Nature, Beasts of No Nation, and South African Voices in Washington D.C. His work is represented in collections such as the South African Embassy Art Collection and the Smithsonian Museum of African Art, both in Washington DC, along with other private collections both locally and internationally.