Exploring history through different perspectives

How do we learn and then explore the history of our countries when we share more than one national or ethnic identity? And what is the meaning of "modernity" in developing countries?

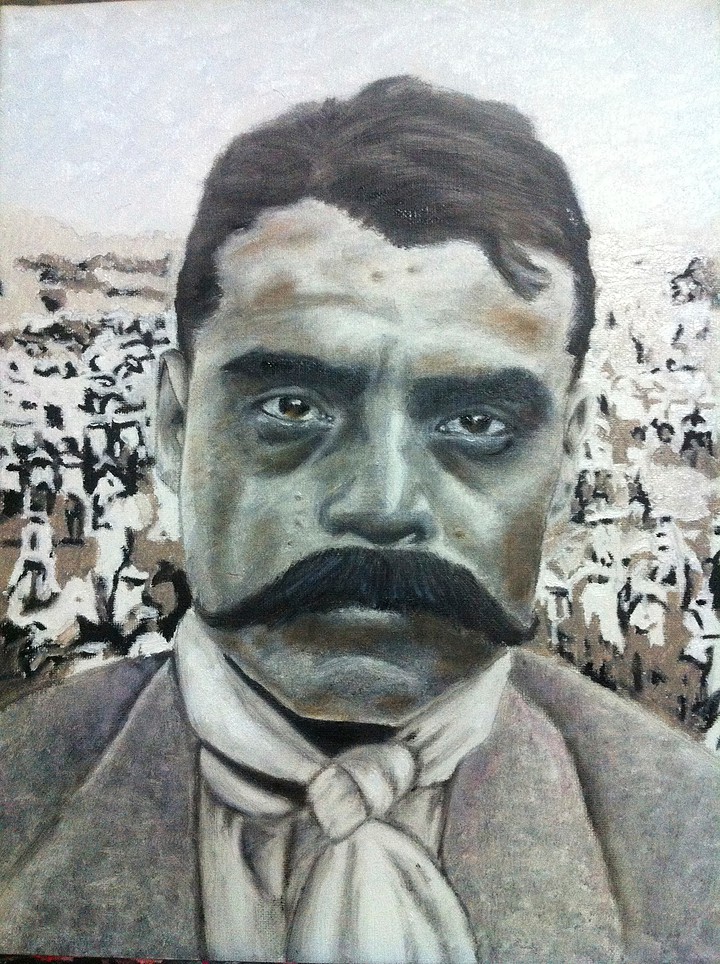

Mexican American artist Eduardo J. Chaidez and Indian American artist Uji Venkat in a conversation prompted by Eduardo's recent works.

Uji: I am most interested in your portrayal of this young armed child. The photographic, pixelated appearance of this painting has undertones of pop art while it is also a portrait of historical significance. I’m not sure if that is the meaning that you wanted from your title, but I see in it the conflict between modernity and tradition. Can you share the historical context of this particular piece?

Eduardo: Thanks for your question.

The historical context is the Mexican Revolution (about 1910-20). Porfirio Diaz' 7-term presidency, which was actually a dictatorship, from 1876-1911, favored foreign investments and markets over native autonomy. The driving force seemed to be the appeasement of foreign markets through commodification of natural resources and who controlled those resources in order to gain prosperity at the cost of a cheap and exploitative labor force.

Mexico underwent a revolution in order to remove Diaz' dictatorial administration that favored foreign investment and trade. The inclination to enter the global economy to rise to prominence left Mexico precariously dependent on the whims of overseas demand. The expanding global competition meant that more exports needed to be made and be competitively priced. This led to the aggressive acquisition of land from rural communities in order to create more cash crops. Cheap labor by peasants maximized profits for the wealthy elite. Often this work force ended up laboring on land they once owned, leading to obvious tensions in the Southern parts of Mexico.

In the North, laborers such as mine workers were abused and paid less than their foreign counterparts. These tensions exploded into a bloody revolution. In the end, in spite of the revolution, proper and just land reform was never attained. The new government eventually monopolized the natural resources, yet the country remained deeply divided by class and income disparity.

The transformation of land into commodity through free or inexpensive labor in order to satisfy a globalized economy gave the ruling elite greedy ambitions for wealth. Porfirio Diaz’ dictatorship planted so many cash crops that people couldn’t even grow their own food on land that they no longer owned. This dependency on export secured Mexico’s role on the world stage. Vast amounts of natural wealth lay within Mexico's borders - yet the country remained incredibly poor.

Many of these issues could also be said of Mexico currently as well and this history is one that is familiar to many other countries of the Global South. I think your read is interesting and spot on in terms of the conflict between modernity and tradition. This notion of Modernity as progress is one that contains a dark underside of exploitation and abuse that I feel like my art grapples with in one way or another.

Uji: Thank you for the thorough explanation! I agree that there is a common misconception that modernization implies progress. I saw it first in India, also a poverty-stricken nation led by a corrupt government, as the rich built massive enterprises and became richer at the expense of the vast majority. However, I now see a growing discord between modernization, mainly in technology, with social progress in the US. Your work addresses social commentary that is universally valid in this day and age.

Growing up in the US, I did not know this much about the Mexican Revolution, as it wasn’t taught in my history classes. But seeing as you were also born here in the US, what sparked your interest in studying Mexico’s history?

I completely relate to the idea of being seen as an outsider in your own country. I hold American citizenship by birth, speak English without an accent, celebrate all of this country's national holidays, and support the US in the Olympics but somehow it is always the color of my skin that indicates my identity. Nationality is masked by race. I’ve had difficulty with my country not owning me in return. I appreciate that you have embraced your cultural and racial backgrounds instead of veering away from them as a consequence of this struggle.

Eduardo: I appreciate the questions! Studying Mexico's history was sparked for the very reason that it isn't taught in history classes, as you point out about your educational experience. Conversely, someone might argue that it's not possible to teach every nation's history, or that maybe that's not a priority in US education. But I think that a response evades the notion of History as a narrative and/or erasure.

Do we learn about the brutality of colonization and its legacies on First Nations peoples? We somehow begin at the 13 colonies and how they were founded by these noble men, but never do we talk about them as owners of enslaved Africans. Issues such as these are buried and the notion of progress is espoused creating this idea that these atrocities were necessary and/or justifiable and just not that important.

Being a first generation Mexican-American was really confusing in this context. I actually internalized a lot of hate about myself as a kid because I picked up on the fact that I was treated differently because of the color of my skin. I think in part this is reflective of the value our society, and by extension our education, places on who and what is normative. Central to my work has always been this dynamic of personal and collective histories.

Ironically, it was through education, when I was much older, where I eventually learned in depth about other histories. Because I wasn't taught them I had to go looking for them. I took courses in US History and Mexican and Latin American (M/LAT) studies in community college and I also majored in Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley (along with Practice of Art).

Uji: I agree with you that even the history that we do study of other nations, as it relates to the United States, is from a skewed point of view. It is interesting the light in which history is painted based on varying perceptions. The US and other countries share the same history but the recordings are different as they are colored by the varying perspectives of the events.

I love that you have chosen to explore the other side, the side that wasn’t readily presented to you. The notion of progress that you cite is clear in your art as well as your writing; I can see that you want the errors of the past to surface so we are not doomed to repeat history.

I love that you have chosen to explore the other side, the side that wasn’t readily presented to you. The notion of progress that you cite is clear in your art as well as your writing; I can see that you want the errors of the past to surface so we are not doomed to repeat history.

Eduardo J. Chaidez holds a B.A. in 'Ethnic Studies' and 'Art Practice' from UC Berkeley, and he is currently a Master of Arts candidate in Visual and Critical Studies at School of the Art Institute of Chicago.