‘Through the Artist Lens: Breaking Barriers in Communication’ | San Francisco, California

Forty-three Master of Fine Arts students of the California College of the Arts presented their theses (paintings, photographs, illustrations, installations, and sculpture), at the Minnesota Project in San Francisco.

“I think artists can save the world” -- Jennifer Brandel says in response to

“Why art as medium for communication?”

Unlike typical gallery showings, where one artist’s work fills an entire room, the CCA theses were presented six to eight pieces per space. As a result, the experience of the viewers is not limited to their intake of one artist’s creation, perspective, and portrayal. Each piece had an individual purpose, question, or presence, but the most interesting part of the show was their cohesive interaction.

Unlike typical gallery showings, where one artist’s work fills an entire room, the CCA theses were presented six to eight pieces per space. As a result, the experience of the viewers is not limited to their intake of one artist’s creation, perspective, and portrayal. Each piece had an individual purpose, question, or presence, but the most interesting part of the show was their cohesive interaction.

CCA thesis student Beatriz Escobar’s piece extends beyond the vibrant floral backdrop, the table lit with projected marquee phrases, and the rolling metal cart of food, books, and other supplies. The whole of the piece is set up for the interaction of the audiences within the space she has created to facilitate communication.

Across the table, Beatriz then has a one-on-one conversation with visitors about how they relate and interact with other cultures. Her analysis originates in the concept of “anthropophagy”, a familiar concept in the Brazilian tradition, which refers to cultural creations as a result of appropriation, consumption and remixing of the creations and inspirations from other cultures, as in a kind of metaphorical cannibalism.

Beatriz explores this idea in reference to the actual consumption of food, as well as of cultural products which are often redefined and marketed. She explores the “consumption of the exotic other,”[2] through acai, Brazilian native berries categorized as a 'superfood', but containing the same amount of antioxidants as blueberries.

The setting itself and prompts of “acai bowls” encourage the initial connection with the viewer.

As part of the piece, Beatriz uses her insights, acknowledging her own bias as a Brazilian woman living in the Bay Area, California, to create an acai bowl to appeal to the palette of her participant, while he or she reads a passage detailing anthropophagy out loud. Here, the viewer becomes a less passive member of a wider audience, he or she becomes a contributor to the art. The reactions and responses throughout the entire process cycle back to Beatriz and she too is part of the growing and developing conversation.

Beatriz pushes the audience to confront their privilege, judgement, and understanding of others within an enclosed gallery space. In a similar space upstairs, MFA student Jennifer Brandel challenges the walls of the gallery through a different personal journey.

Jennifer exhibited a mixed media installation called Nimesiscape. A wooden frame--planked orange backing for twenty-five square papers--rises over viewers’ heads. While the physical creation is a collection of samples from nature, square perforated papers, vertically mapping a recreation of the outdoor space, with a compilation of observations, along with the process and methodology of getting it there, completes the art.

Inspired by her love for nature and curiosity about environmental impact, Jennifer buried perforated paper in a protected National Park. The park serves hikers and thriving livestock alike, “a sanctuary and a commodity.”[3]

After a period of time, she dug up the paper, taking care to preserve the samples of earth that had collected, and recreated the terrain in the vertical piece that is presented in the gallery.

Importantly, Jennifer maintained a one-to-one scale in her twenty-five square unit, displaced terrain installation and created a corresponding map. In order to further the audience’s immersion, Jennifer also catalogued her chosen observations and experiences in the booklets placed on the back of the vertical piece.

The process of choosing what content to capture in writing for the piece was also very intentional. She compiled voice recordings from each site visit which she then broke down, categorized, and copied by hand.

Writing and mapping, along with the visual and physical presence of the large sculptural piece, collaborate to appeal to each of the senses. Acknowledging that one cannot know something without being there, Jennifer sought to recreate her outdoor experience for the gallery audience. By means of these components, the original space within the national state park which Jennifer catalogued, organized, and restored, presents questions about human nature--the desire to create structure and to preserve, as well as what comprises a commodity.

Frequently asked what the piece means, Jennifer says, “I didn’t want to give all the answers because I didn’t have all the answers, and I wanted to leave space for inquiry.”[4]

While creating her piece, Jennifer was analyzing the living cycles of consumption and destruction. By presenting a tangible and proximate interaction, she encourages viewers to do the same as participants of the work.

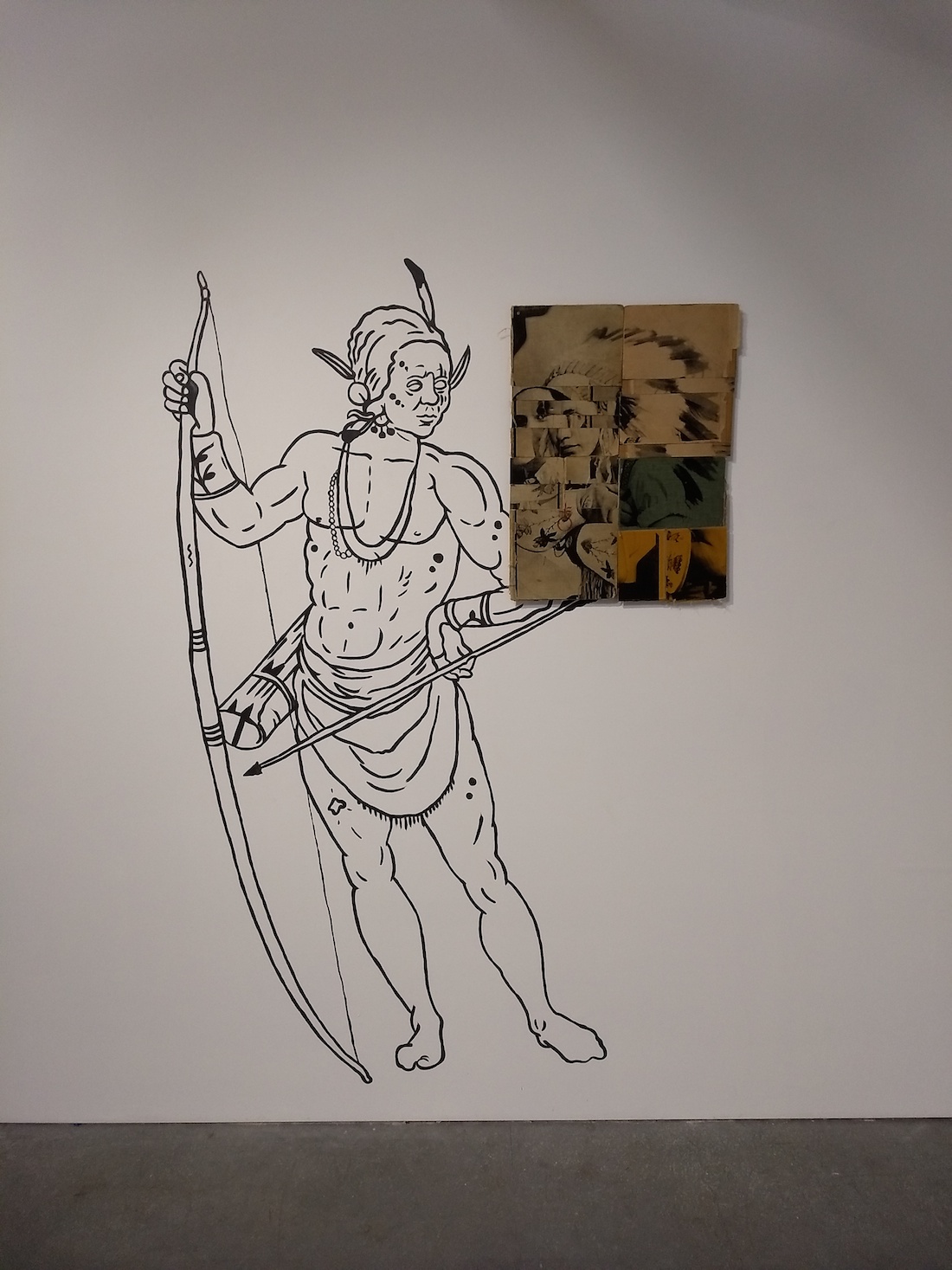

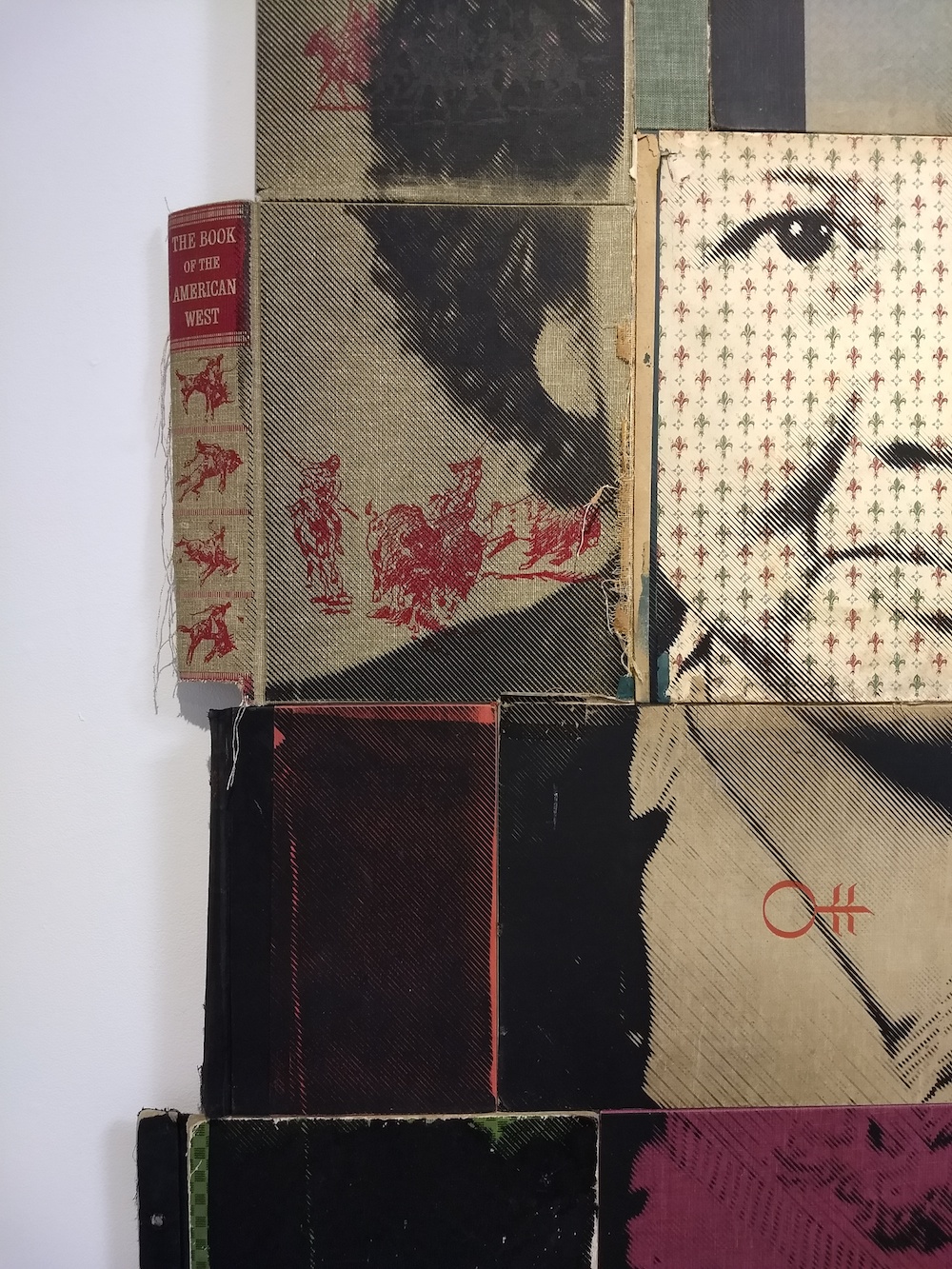

Across the room, Keith Secola’s exhibit beautifully contrasts black and white outlined misrepresentations of Native Americans with a pieced together colorful history of printed books and family photographs. He juxtaposes common portrayals assumed by the Western world with his own experience and collection, “questioning the power of text, image, and persuasion.”[5]

Keith found his natural path for communication through his art from exposure to Native American artists at a young age when his family traveled with his musician father. He explains the dual nature of his identity, his Northern Ute blood colliding with his urban upbringing, “When I’m outside of my community, even at a young age I would face racism and ignorance from non-native people. So finding a way to represent myself was always difficult. Speaking visually through art became a way for me to do this.”

He explores the representations of Native Americans today as “native people who are either misrepresented or not represented at all.” And “it became important to question this issue more in his work and projects.” [6]

Once again, the audience is presented with an external and internal view, the external being the Western stereotype that is marketed, and the internal being the real facts and stories of the people.

All three artists--much like the other forty CCA students who presented their MFA theses at the Minnesota Street Project--extend their creativity, passion, and curiosity to their audience. Jennifer’s faith in the open mindedness and design thinking capacity that artists often possess is exactly why “artists can save the world” in collaboration with experts from other fields. By opening conversations, these students demonstrate art’s potential to inspire discussion, redefine misconceptions, and analyze within as well as outside oneself.

Notes: [1] The Minnesota Street Project is situated in the Dogpatch district of San Francisco. It houses galleries and studio spaces for local artists, seeking to create an international art community destination in synergy with the Silicon Valley technology hub central to the region. [2] In conversation with Beatriz Escobar [3] Artist Statement, Jennifer Brandel [4] In conversation with Jennifer Brandel [5] Artist Statement, Keith Secola [6] In conversation with Keith Secola