‘To Labour Together’: Working with heart and collaboration | Maputo, Mozambique

EAS contributor Valerie Amani, from Tanzania, reflects on her experience at the ColabNowNow 2018 residency program in Maputo, where she encountered and interviewed artist Hugo Mendes.

Why is art important? I ask this question coming from a historical cultural background where art and functionality are synonymous; a pot - however beautifully adorned and detailed - is still first and foremost just a pot; its value intrinsically tied to usefulness.

The idea that an object with no functional use, should be placed somewhere just to be looked at and admired, is by far a new (and strange) one in most local African communities. It may be because of this history that art, as it is presented to us (via white walls, and effervescent lighting), would come across as foreign and generally misunderstood.

Collaboration, however, can be used as a tool to merge the past and the present, as it is rooted in community and group practices of creating – be it beadwork, musical celebratory ceremonies or pottery. A labour for one becomes a labour for all. It is perhaps why young African artists, including myself, have thrived and continue to thrive off constant collaboration and group innovation.

9 artists from 7 countries in 1 house for 10 days –the premise of the ColabNowNow residency program founded by the Southern African British Council. The 2018 program was based in Maputo, Mozambique, running in conjunction with MaputoFastForward, bringing together artists from East, West and Southern Africa as well as the U.K. All with one purpose – to exchange and collaborate. The residency ended in a group exhibition and was filled with a cultural explosion of music, food, gallery visits, talks and my favorite - interacting with the local artists.

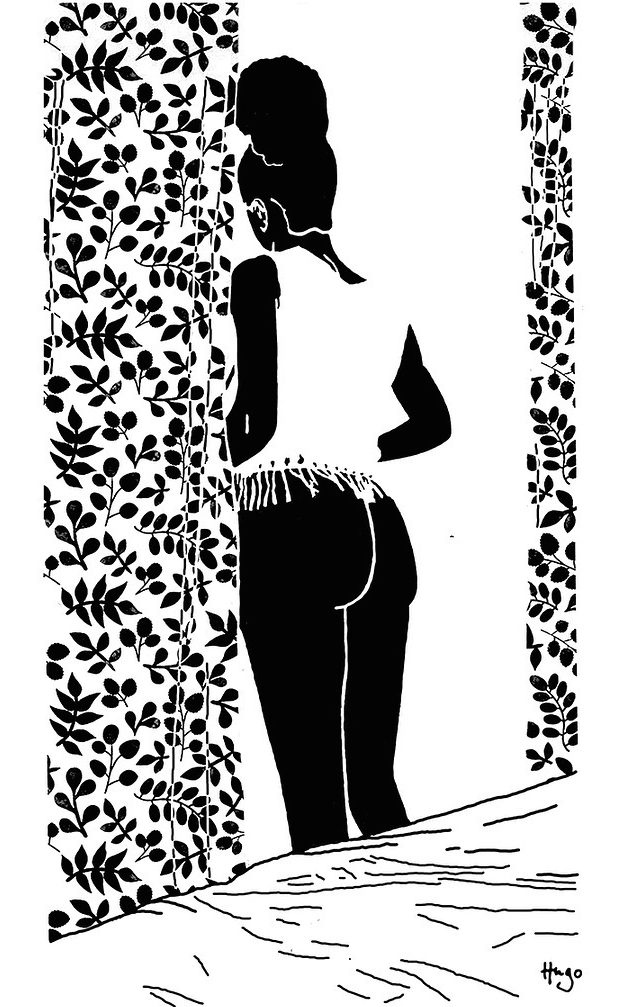

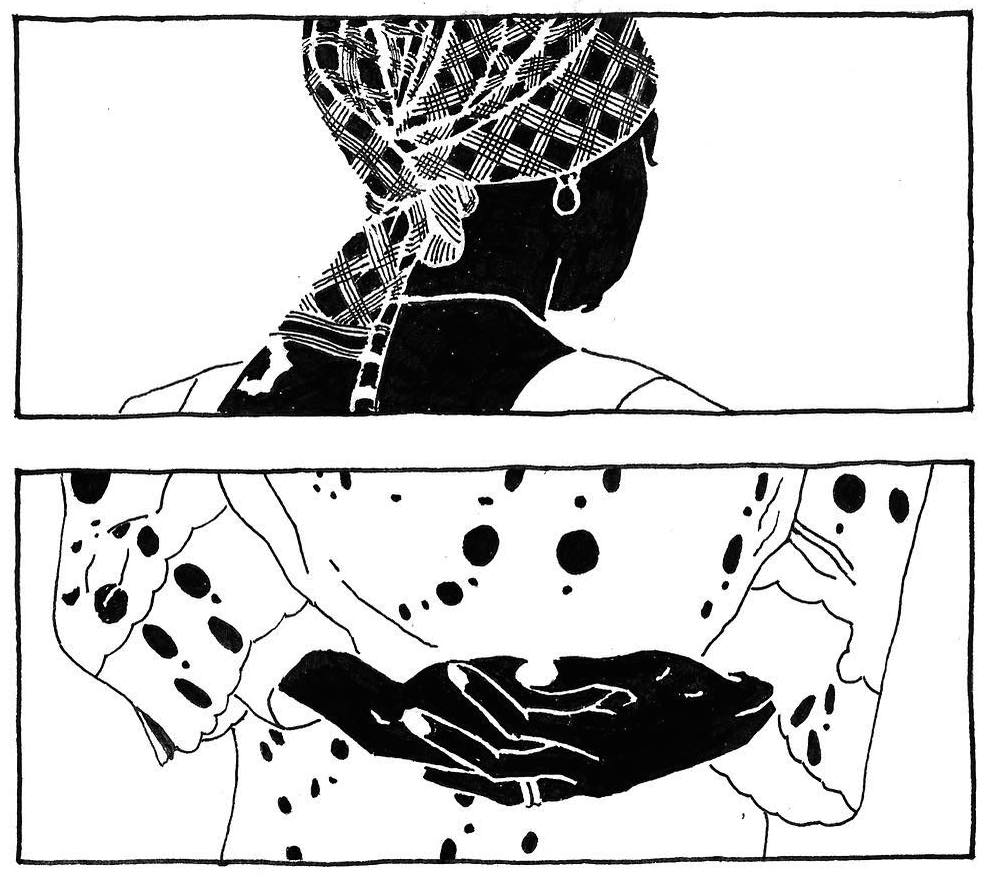

During one of our artists’ exchanges, we walked into an exhibition titled “Sunday Nood” by Hugo Mendes, a young digital artist known online as Psiconautah. I immediately connected to the images because of their intimate and subtle rebellion: female figures, naked and aware of their observers.

Hugo himself has this gentle fire and as one of Mozambique’s emerging artists, I wanted to find out more about his journey in relation to the local art scene.

Valerie: Any comments or points you would like to share before we start?

Hugo: English is not my first language so sometimes I say stuff that are funny – but as long as the feelings are transmitted it’s ok (he laughs)

Valerie: How did you first start creating art? Why is it important to you?

Hugo: my older brother used to draw everywhere (and ruin books while at it). Mostly comic book characters, action heroes and yeah, I started drawing imitating him. Drawing has become important to me because it’s like a meditative state, a way to tune out the whole world and be in the moment.

Valerie: What is your experience as a young artist in Mozambique?

Hugo: People here don’t really believe in visual arts; music and dancing is more popular because of our cultural heritage. I guess people say it’s difficult to appreciate art when we have major societal issues. Most people believe that you will only be successful if you make foreigners your target market; foreigners have the buying power. But I see this as an opportunity for young artists - to change this and stop selling ourselves short.

Valerie: Any trends in the art scene?

Hugo: In art it is more about social circles; we have groups of artists collaborating together, hanging out together and supporting each other.

Valerie: Many Mozambican artists seem to be influenced by industrialization (metal, recycling objects, abstract multimedia paintings) did this ever apply to you?

Hugo: In a way my approach is similar. I only use two colors as a necessity. When I was starting out I didn’t have money to buy a lot of materials so it was easier to get black ink. This forced me to think outside the box as to how I could do things that are interesting and different. I believe if something looks good in black and white, it looks good in any colour.

Valerie: What are some of your challenges as an artist in Mozambique?

Hugo: Figuring out how to reach the majority. I am very active on the internet which most people don’t have access to. They might also feel intimidated to go see my shows at the gallery. They perhaps think that those kinds of places are expensive and not for them.

Valerie: Can you tell us a little more about the content of the work you exhibit?

Hugo: I make things that I would like to see and also how my experience shaped me. I never planned to have a career in art. I was actually studying to be an engineer.

I just decided to do things that I wanted to see, that I’m inspired by – I always find it’s amazing that people actually like the same stuff that I like.

Valerie: Why is contemporary African art necessary in our societies?

Hugo: Cultures evolve, and as young artists we have to document it and bring it to the future. We have to take charge of our own narratives and stop waiting from motivation to come from other places.

Valerie: Lastly, what advice would you give other young aspiring artists?

Hugo: Believe in yourself when no one else will, have patience, do it for yourself and do not compromise.

Hugo’s warmth and openness to share is a reflection of most of the artists that you will find in Maputo; which is what leads me to believe that it will surely become one of Africa’s leading contemporary art hubs. The unspoken confidence, the vibrancy of community and the feeling of welcome is so contagious one may not want to leave – evidence that the ColabNowNow and MaputoFastForward mission was achieved by creating an environment that can transform a different country into a home, and a house full of strangers into a community of friends.

Art continues to unfold itself as a necessity because of its power to bring together. It peels off the boundaries that our everyday lives work so hard to construct – language barriers, gender barriers, ethnic barriers - leaving us open to understanding and ready to find an anchor through another’s vision.

African art is still as practical and perhaps even more valuable than it was from its origin. Its practicality merely shifts from everyday household usage to a universal way of translating our communities’ stories, debunking stereotypes and diffusing propaganda. Art perseveres.

As Hugo Mendes put it, “as long as the feelings are transmitted, it’s ok,” because it is with feelings, that thought is born and mindset begins to evolve.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author: Valerie Amani is a Dar es Salaam born and based fashion designer, makeup artist and graphic designer. She is the founder and director of Kahvarah, a boutique fashion label that focuses on the African narrative; the co-founder of R.R. Creative Agency, a creative consultancy which has placed her behind the visual language of various brands in Tanzania, as well as the visual art program manager at Nafasi Art Space where she curates exhibitions and workshops. Valerie combines digital art with her love of writing to tackle issues on neo-colonialism, environmental awareness and feminism.