‘Living in Digital Utopias’: On Existing and Art-Making | Tanzania

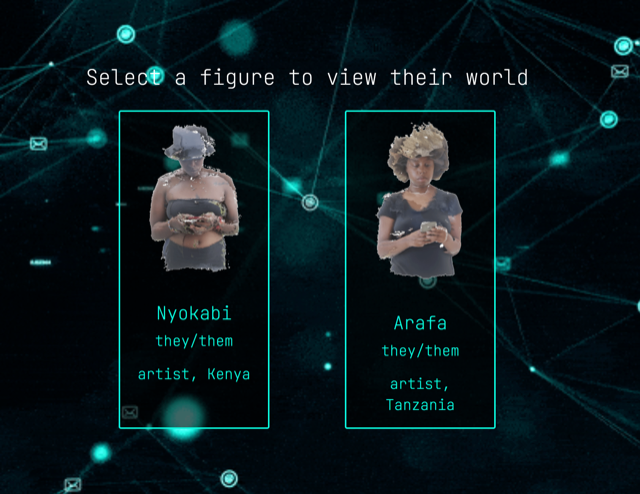

EAS correspondent Valerie Amani writes about her conversation with artist Arafa C. Hamadi, a non-binary artist from Tanzania. Their discussion centers on Arafa’s art practice, exploring themes of identity, body and belonging within digital media and virtual spaces.

“Hello, I’m Arafa. I am a non-binary artist, living.” Those are the words that greet you as you enter Arafa’s digital Artist Residency page – the word ‘living’ lingering, almost rebelliously.

In this instance, what does it mean to live? Living as your true self in a society that has carved you out to be an ‘other’, ceases to be just living; it becomes an act of resistance. As a self-identifying queer, non-binary artist, Arafa makes part of a necessary ecosystem of East African artists who just want to live.

In their artistic practice, Arafa explores themes of belonging, identity and body through digital media and virtual spaces. As a fellow Tanzanian artist, who understands the cultural implications of ‘living’ as an act of resistance, I was curious to know more about their work and how it has shaped the way they interact with the world.

Arafa takes me through their artistic journey, starting from a high school assignment that led to their first encounter with anatomy through the works of Peter Elungat - an artist whose work playfully represents the body. They also mention how intimidating it was when shifting from primarily working as a graphic and set designer that received briefs, to having no briefs or guidance as an independent artist.

On asking Arafa what has come to be their artistic process, they commented on how much their process changes depending on their location and what is happening in their life.

“I’ve moved away from my previous more methodical process. It was terrifying creating my own work – what do you do without a brief? [they laugh] I have found that the confusion and questioning of the self at the beginning of creating, has become my art. My process has been about reflection, and what questions I have been asking myself, then finding artworks that have been answering these questions – artists I follow on Instagram, my friends. I interrogate myself; I find precedence; then I let myself ‘vomit’ [they laugh] this physical artwork out.”

The metaphorical “vomiting” alludes to how Arafa aims to use the rawest version of their feelings and emotions without much editing; their works coming across as intimate and vulnerable virtual diary entries. In one of their earlier pieces, a poem titled 'I,'I Arafa writes:

“I,

I am not a ringing noise

screeching over the night, like a siren,

an unbolted screw yearning for deliverance, as if your hand alone

can hold me in place.”

This piece was written before they identified as non-binary and paired with a video they recently made. The combination of past and present work are significant in how we reflect upon changing identities.

“In the piece I read out a poem – I am interpreting an Arafa that existed then. The Arafa that existed then did not identify as non-binary, but had felt that they were at the cusp of understanding and somehow moving away from womanhood. Me reading the poem, I can relate to that person.”

It is evident that the self is at the center of Arafa’s work, a self that despite having to find ways of existing beyond the physical, still has a tangible sense of acceptance and self-awareness. On speaking about how they have used digital media and the internet, it is clear that the digital realm has provided a means in which they can live.

“As non-binary people, according to the government, we do not exist. We are not counted in the census. I cannot report a hate crime against me – I would get arrested for being homosexual. The only place I can claim myself is the internet. I can put the rainbow flag in my bio and I can write about my experience on the internet without feeling too unsafe. And if I do feel unsafe, I can delete it, and it becomes non-existent again.”

This is another act of necessary resistance, resisting being silenced; especially when your voice and history is one that has been stifled before. Arafa is conscious about the role that art plays in how we remember - one of their most recent art pieces being an amalgamation of the present and past. It is an old Swahili Dhow, painted and covered in symbols including the non-binary symbol.

The piece is fittingly titled, Kujiona, which is Swahili for “to see oneself”. The work is accompanied by a video piece in which Arafa converses with a local man who also identifies as Queer, their conversation centering on the history of homosexuality around the Swahili coast.

“The conversation starts with me saying, I feel like we have no queer history, but then eventually we realize that it’s there! It’s there because we have the [Swahili] words for it. It’s there because there is this taboo that surrounds it. It’s there because my grandmother’s homophobia is specifically different from western homophobia. [It’s there] even in spiritual stories of the baobab and the ocean; maybe those are queer stories. I see myself in those stories and, thus, I claim them for myself.”

There is a certain peace that comes with being seen and being acknowledged, a peace as a result of not having to constantly tell people who you are, but knowing that they just see you. At the heart of Arafa’s work, they are showing us who they were and who they are - while encouraging us to do the same - show ourselves.

“If we can see ourselves, and we are inspired by the stories that we hear and the history that we learn… is it so bad to want to see [more of] ourselves so badly that we start creating our own stories?”

In Arafa’s latest work Letu, a product of an online fellowship with the Institute of Creative Arts (Cape Town), they have not only created their own story but also built their own world, their “utopia”. In this work Arafa uses the virtual space to live freely, combining their favorite sounds and landscapes where both Arafa and another non-binary friend exist, captured digitally - forever in a state of peace.

As a final reflection on the importance of living, especially living as a person who creates, I ask Arafa what advice they would give to artists who are in a space in which they do not feel seen. Arafa answers by saying that one should keep identifying moments that feel important to them and record those moments by whatever means possible. “Yourself, and your own experience is a worthy subject to explore over and over again,” they say, and I agree.

As artists we have this wonderful gift that allows us to manufacture worlds, write truths and make our own history - it is vital to remember that we are important, that the work we do is important. It is vital to keep living, to keep resisting against governments that isolate and ignore queer bodies, that criminalize ways of existing. It is vital that we keep building the realities we want to exist in, even if that means starting online first.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Arafa Cynthia Hamadi is a multidisciplinary artist working in Tanzania and Kenya. They create artwork in various mediums that address the intersections of the conceptual and the physical, as well as the ephemeral and the permanent, in hopes of provoking their visitors into considering their daily realities. Arafa’s work also explores their queerness in relation to space and occupancy. They work in the realms of 3D design, graphic design, sculpture, architecture and sound.

More of Arafa’s work can be seen through their portfolio and on Instagram: @arafabuilds

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Valerie Asiimwe Amani is a Tanzanian artistic explorer who uses words to paint pictures, pictures to deconstruct daily interventions of emotion and emotion to create videos. She is currently an MFA candidate at The University of Oxford, researching and creating work around the intersection between art and modern spiritual practices.

Instagram: @ardonaxela | website: www.valerieamani.com