Art & Human Rights: Reflections on the Exhibition | International

We asked Valerie Asiimwe Amani, artist, curator, and long-time EAS correspondent, to review and offer her thoughts on the Art & Human Rights exhibition. We are pleased to present her insights

and reflections here.

Art's function as a political tool is not a new concept - from 15th-century military strategies, to propaganda paintings of irrelevant monarchs as proof of legacy and dominion. However, the use of art as a tool for resistance and activism has only become a global movement in the past 60 years, with roots in the Anti-Apartheid and Black Consciousness movements.

In the contemporary landscape, activist art has been catalysed by access to smaller cameras, phone video functions and sound recorders. Fueled by the increasing awareness of injustices shared incessantly on social media platforms - at times it seems all too overwhelming to sympathise and properly engage with the violations of people's rights. Most of us have become desensitized; caught between misinformation, guilt and a feeling of global hopelessness.

The work presented in the exhibition is perhaps a way to reintroduce us to what it means to be human, trying to bridge the gap between desensitisation and empathy. It is clear that most of us, universally, understand our rights. The exhibition, however, offers a way to slow down and realise that it is not so much about human rights (the right to be safe, healthy, sheltered, etc.), but more so the devastation caused by being constantly denied the rights you are supposed to have. Scattered in the exhibition are also small reliefs in the form of offerings of faith, celebrations of women, and an underlying message that things either can change, or must change.

The first artwork we are presented with in the exhibition confronts us with the thieving nature of child labour, challenging what our responsibility to children should be in a world that favours fast fashion, fast food and overnight production. Death of Heroes by Anirban Mishra is a challenge to the right that education should be made accessible to children, the apparent holders of the future. He presents a cyclical system of oppression that stifles the youth's ability to experience the curiosity of childhood, preventing them from even dreaming of becoming heroes in the first place.

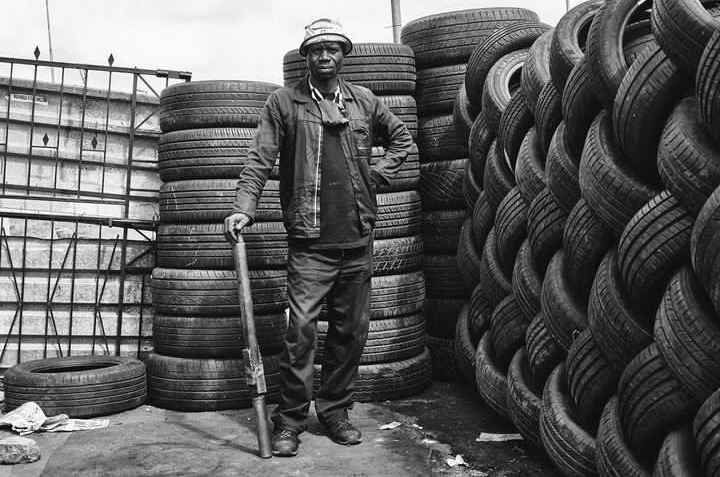

Other prominent themes come in reflections on consumerism, labour, and poverty. Works from India, South Africa and Russia illustrate the failures of our economies, showing a familiar disparity caused by lack of access to work, education and land. Gugulethu Ndlalani’s photographs view labour as a communal act of survival. The men, seen through his lens, depend on the work they can get within the township of Soweto (South Africa) to not only feed themselves but their families. They form part of a necessary informal economy, implying that the formal government economic system has overlooked them and/or failed.

The state/government seems to be at the centre of many of these injustices. When the politics of negotiating space, race, and liberation are involved, regimes of extreme control often use tools of violence as a way to keep people in order. The term ‘Human Rights’, becomes an instrument of wishful thinking when confronted with the reality that most governments have been allowed to disregard human rights by the very organisations that established them. Effectively put by Indian author and activist Arundathi Roy: “It's a battle of those who know how to think against those who know how to hate. A battle of lovers against haters. It's an unequal battle, because the love is on the street and vulnerable. The hate is on the street, too, but it is armed to the teeth, and protected by all the machinery of the state.” (Azadi, Arundathi Roy, p. 178)

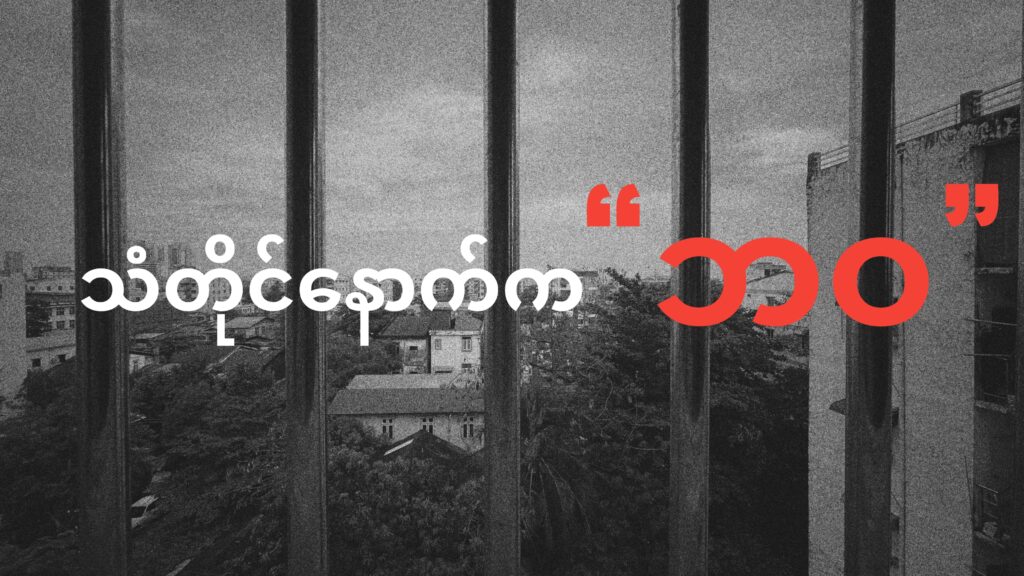

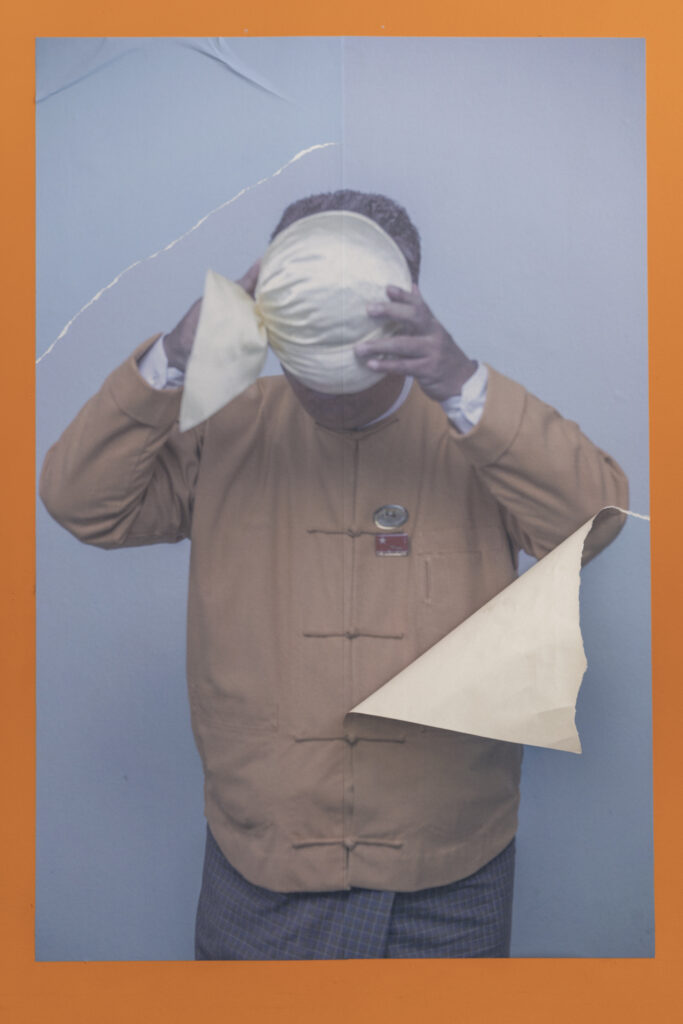

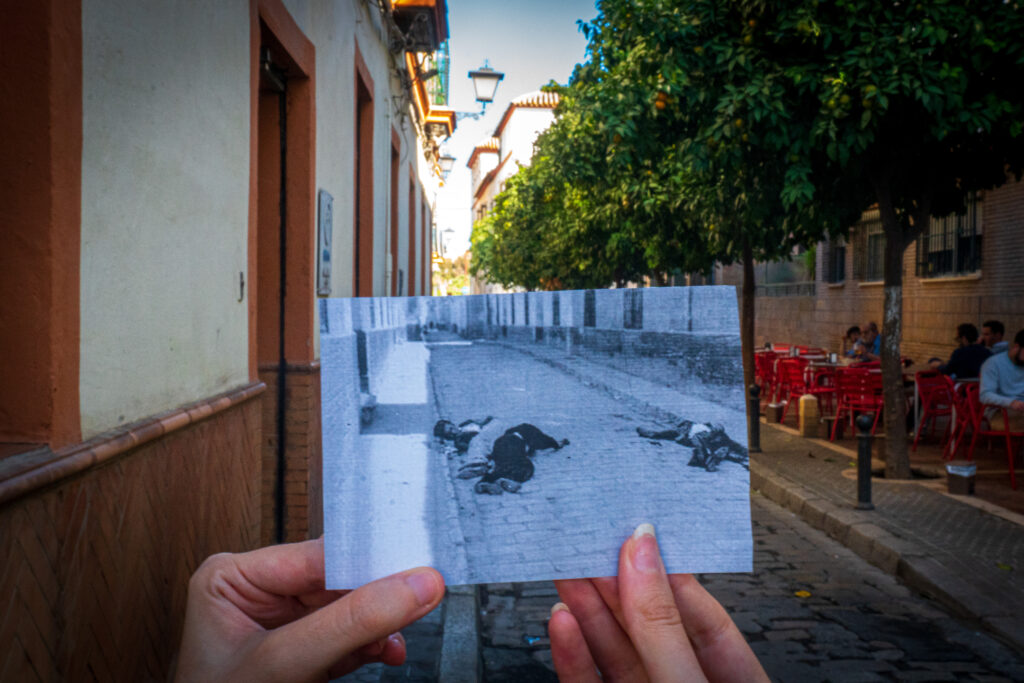

Reflecting on Roy's sobering words, if the hate remains on the street, and the battle continues to be unequal, does creating art about it then become a work in vain? Perhaps in some instances, it does; but, more often than not, art becomes a record keeper forming a foundation for change. It can inspire, educate and shed light on current genocides that the ‘world media’ has turned its back upon. One such work that truly moves is Father’s Portrait, by an artist who in order to protect his identity goes by the name of Sai ▇▇▇. On reading further on this work, which is part of a larger collection from Sai’s Trails of Absence project, it becomes clear that creating this work places a threat to Sai’s life while also validating it, with his refusal to be silent. Courageously retelling the atrocities carried out by the 2021 Myanmar military coup, at the centre lies a son who has been violently separated from his father, amidst experiences of a broken family and country. Like so many others, the fear of execution lingers over the works, as Sai also grapples with the lack of help he has received from foreign states.

The artwork becomes an ode, a diary of accountability, evidence of crimes committed - as well as a very real depiction of the junta’s blatant disregard for human life. If he can’t have his name, he risks his life to at least hold on to his family's story, told through his artwork.

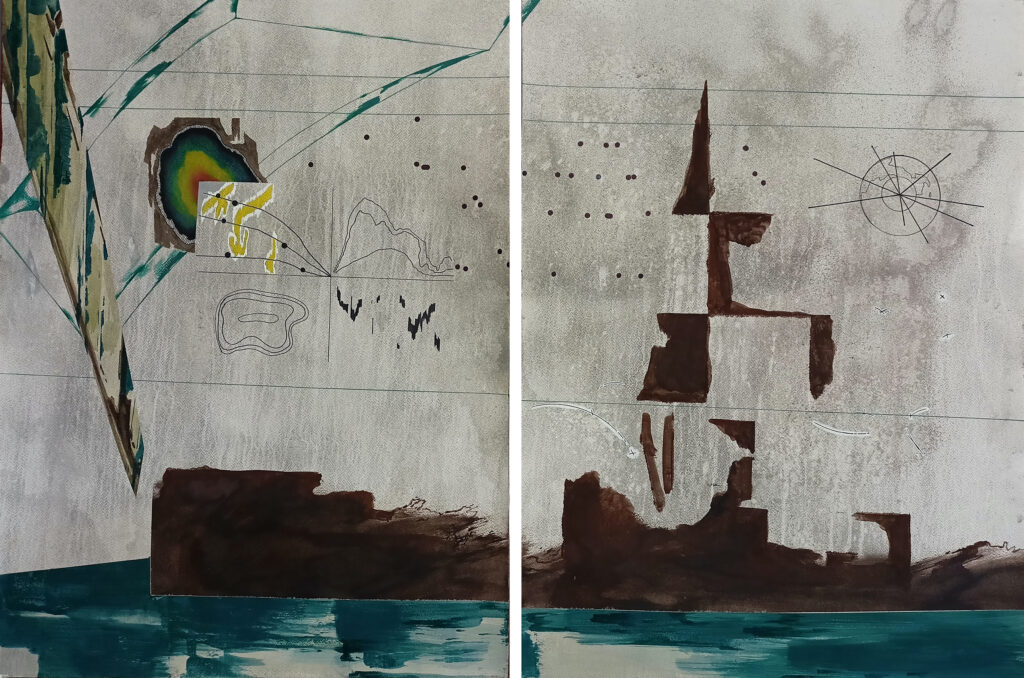

Right: All I Wanted for Christmas Were Athracite and a Hail of Bullets by Caitlin Mkhasibe | South Africa

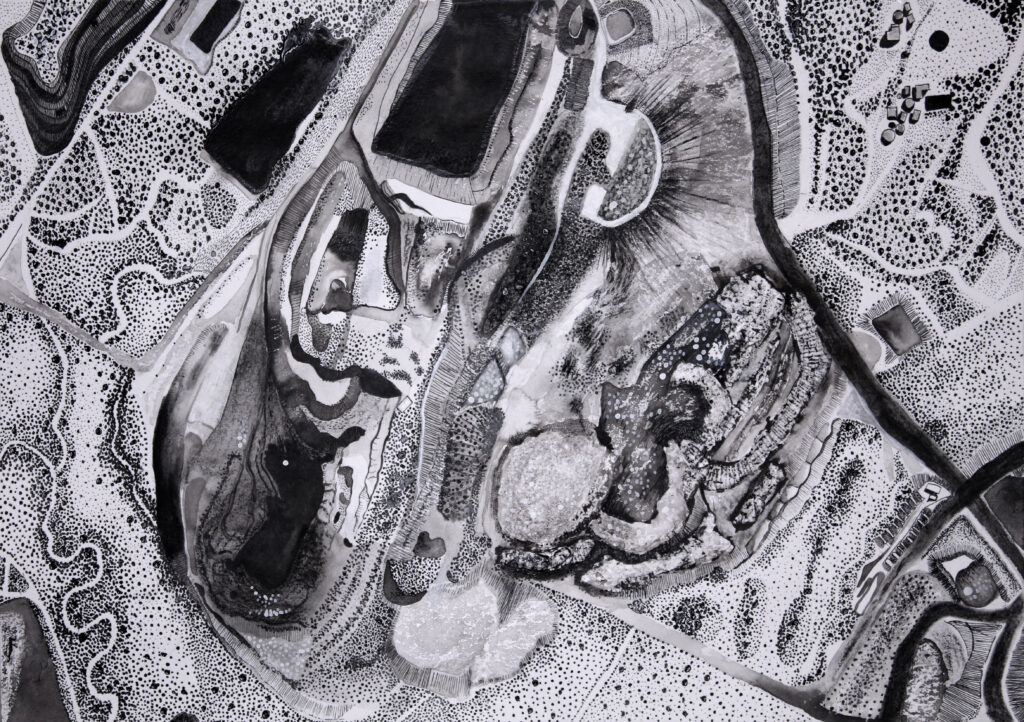

As with any act of violence, there is always a perpetrator and a victim. It is much clearer in cases of war crimes to know who lies where; but when the perpetrator commits crimes that cannot be seen, then it almost seems that these oppressive acts can be ignored. Such is the case with ecological disruptions and climate change, which should also be seen as human rights violations. When considering the victims who depend on the land to live, the people who have no homes to defend themselves from the elements, as in the case of the migrants and the mine workers represented in works by Sourav Haldar and Caitlin Mkhasibe. What do we make of the adopted consequences the Global South has to pay as a result of feeding the economic systems of the Global North?

It comes as no surprise that, as I write this, my instinct is to end with some sort of resolution or token of hope to hold on to. In actuality, the truth is unsettling. The injustices that persist, continue to leave deep and open scars within families, communities, and countries in the name of power, control, or religion. We must be unsettled in order to avoid complacency. So perhaps it is much better to end on an unsettling note.

What this exhibition has succeeded in doing is presenting an array of ways that people relate to their humanity, and how they feel that humanity is valued and protected. The exhibition sets forth difficult truths, with real stories told by artists through their artworks. In an ideal world, we would all hold the basic belief that we are each accountable for one another's well-being. Unfortunately, we do not live in an ideal world. Despite those of us who hold on to bravery and love, it is not enough. Perhaps the question that still lingers, and has been lingering throughout history, is what would be enough? What would we need for human rights--human life and the greater good--to become more valuable than power? Who do we look to, and how can we bridge the widening gap between what human rights should be and its apparent invisibility in so many places throughout the world?