How Context Changes the Art Experience

Reed College | Portland, Oregon

Emergent Art Space’s inaugural exhibit, last June in San Francisco, Crossing Borders, put the viewer both in direct physical contact with the art and with fellow viewers. As EAS grows and exhibitions continue, this opportunity for interpersonal interaction and dialogue about the art will become more regular.

The social sciences help us understand these encounters.[1] The responses are even more predictable in a context, that of the art world, often understood as elitist. When you or I are in a gallery, or a museum, these phenomena will motivate certain discourse and check other.

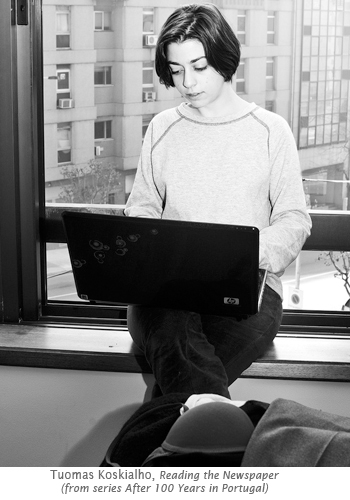

Let’s consider how psychological and social phenomenacause discussions to go unspoken.[2] Or, put more plainly, let’s consider how our feelings make us silent. This interests me because EAS provides an alternative social space to view the art—where the social pressures and motivations have a different effect on us. I, of course, am referring to the Internet. This enables, I think, a viewing of art that, at the immediate moment of exposure, is more private than what is available in the gallery. This is the critical moment because, I think, it is when our schematic approach crystallizes. Our framework for understanding the art is determined in this instance. What are the effects on the non-discourse, on the public silence, when we first consider the art in this alternate setting that manifests this alternate schematic approach?

Let’s consider how psychological and social phenomenacause discussions to go unspoken.[2] Or, put more plainly, let’s consider how our feelings make us silent. This interests me because EAS provides an alternative social space to view the art—where the social pressures and motivations have a different effect on us. I, of course, am referring to the Internet. This enables, I think, a viewing of art that, at the immediate moment of exposure, is more private than what is available in the gallery. This is the critical moment because, I think, it is when our schematic approach crystallizes. Our framework for understanding the art is determined in this instance. What are the effects on the non-discourse, on the public silence, when we first consider the art in this alternate setting that manifests this alternate schematic approach?

I have no answer, but I have a guess. Or rather, I have a hope—which probably exists only because I find the elitism and pretension of the art world super lame. When alone in front of the computer screen, our initial schemata for experiencing the art (again, the way we immediately consider the art) will constitute itself differently than when we view the art in a gallery or a museum, together with other people. A framework for understanding the art will thus manifest that mirrors our framework for understanding other things we see on the Internet.

I have no answer, but I have a guess. Or rather, I have a hope—which probably exists only because I find the elitism and pretension of the art world super lame. When alone in front of the computer screen, our initial schemata for experiencing the art (again, the way we immediately consider the art) will constitute itself differently than when we view the art in a gallery or a museum, together with other people. A framework for understanding the art will thus manifest that mirrors our framework for understanding other things we see on the Internet.

Of course, the Internet is also a social setting with its own experiential consequences, but it is perhaps also more welcoming than what is available in the art world. Think about how you react to a YouTube video, compared to how you and your friends react to a painting that hangs in a gallery. Think about what is available for you to react with.

My independent variables: what the viewer says while initially viewing the artwork in the non-social settings. My dependent variables: what the viewer does not say in the gallery. This is a hypothesis about (a) the significance of first impressions and schemas, and (b) the disruptive effect of new sites of discourse. It envisions a world where we talk about art, unencumbered.'

[1] A more developed analysis would enumerate these psycho-social responses. Brevity precludes any decent attempt at justification, but I’m considering, among others: social identity theory, confirmation bias, and theories of social obedience. [2] This line of argument is inspired by Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality.__________________________________

Jacob Canter is a Social Science student at Reed College, Portland, Oregon. In this piece he explores some of the differences between looking at art in person and looking at art on the Internet. What we see is always affected by the context in which we see it, by the way the “first impressions” become the framework through which we see. When we look at art in a gallery, or museum, Jacob’s claim, the social setting allows certain responses, and precludes others. When we look at art on the Internet, instead, no such social conditioning constrains our responses.