A Studio Visit | Manhattan, New York, US | Part One

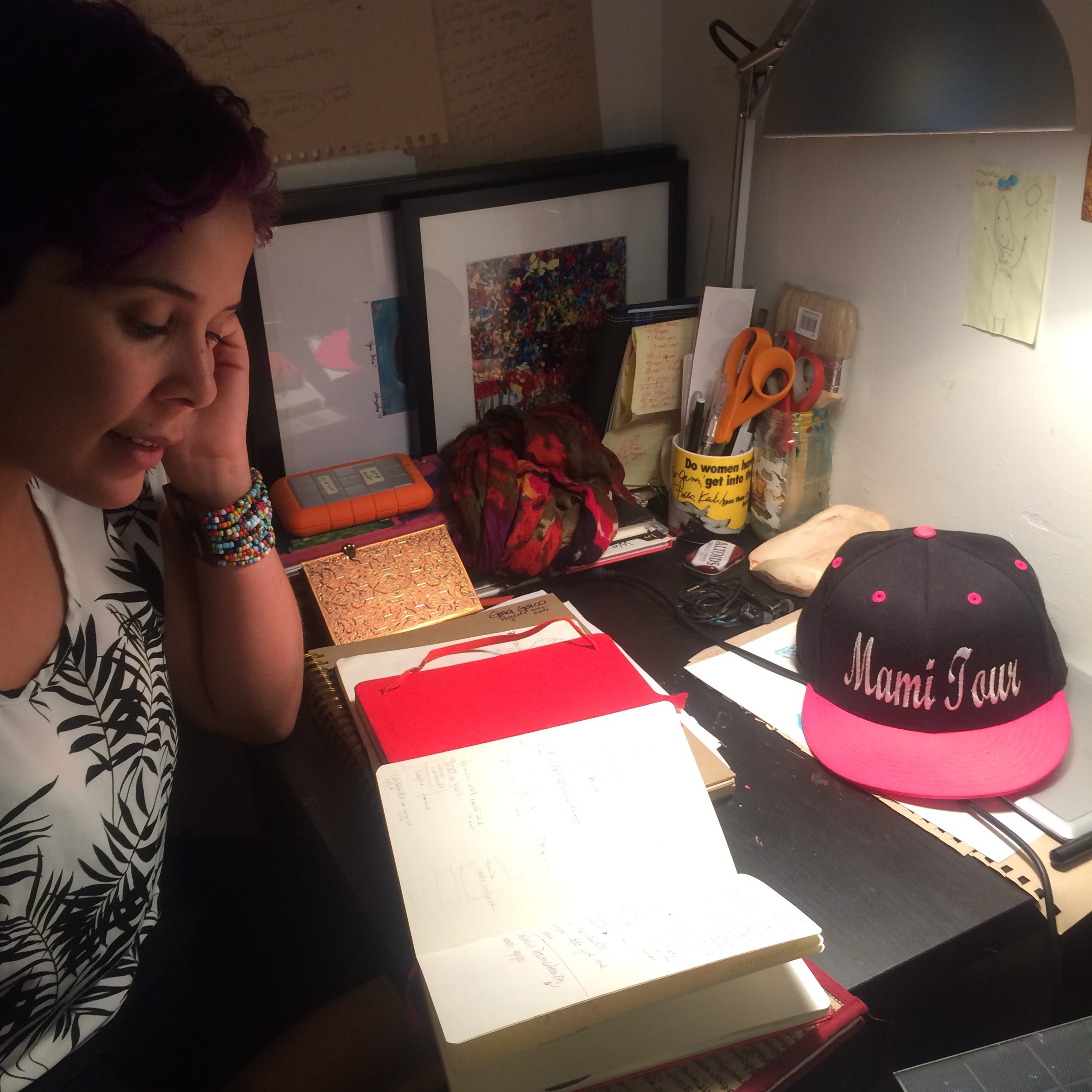

EAS contributor Emma Drew recently visited artist Gina Goico in her studio/apartment in Manhattan, where Gina talked about her artistic practice as well as her experience as a Dominican artist in the US.

[See Spanish translation below]

In the drawings, the pellizas hang heavy, thick carpets cascading down the wall and on to the floor, a deluge of colored fabrics. These are plans for an upcoming project; the pellizas already realized, which drape the walls, the furniture, the back of a chair, the radiator under a windowsill, in Gina Goico's living room, are getting there. In her undergraduate years—not that long ago—the hand-made mats, fashioned out of a stretch tarp or burlap and strips of fabric (all elements likely previously used), carried a defiant message, or a scantly-stylized image of a vagina—“a raising of my finger,” she qualifies with a smile, to art school small-mindedness. Today, no less charged with feminine testimony, they bear the stories, told in the time and space of their making, of scores of other women.

The pelliza project, wherein Goico invites people to join her in weaving by setting up in public settings (previously featured on EAS, see here), was conceived of as the creation of not just a traditional, decorative if utilitarian object, but of a place for women and a space for conversation.

When performed in bodega-cafes in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, her hometown, those conversations often turned to personal matters, relationship-talk, and stories of domestic violence. “It came out naturally,” Goico says, of the shared experiences of everyday violence from spouses, lovers, and male family members. The Dominican Republic, she noted, has one of the highest rates of femicide—the targeted killing of a person because she is female— in the region; in not-so-distant years it has placed in the top ten worldwide. In providing just the opportunity to talk, Goico wants “to guide the [larger] conversation around safe spaces for women.”

Besides the pellizas, Goico's New York apartment-cum-studio is adorned with other evidence of her practice: sketch-filled notebooks, paintings from her days at Parsons School of Design, and posters advertising her socially-minded performances, one with the pitch-perfect imagery of the Dominican clubs she critiques as sites of machismo and female exploitation. Looking from wall to wall traces the components and steps of the larger, longer process of establishing #ATABEY, a research initiative, community outreach program, series of installations, performances, and discussions, and all-around platform for addressing the politics of womanhood and intersectionality—that is, of being a woman and many other things—in the Dominican Republic and abroad, in diaspora.

What has become quite conceptual in nature and aspirations was initially a countermeasure to such ways of thinking about art in the first place. When Goico moved to New York City to finish her BFA at Parsons School of Design, the conceptual strain of art espoused by professors and duly followed students felt in stark contrast to the traditional fine arts school she had attended in the Dominican Republic, where, for example, hyperrealistic drawing and polished beauty took precedence. The transition to the New York art world often meant a confrontation between ideas and imagery, a false dichotomy to which Goico admits she responded strongly. Her work at this time, including the first pelliza, was “a little bit reactionary in regards to what I was [being] faced with, starting with the question of why do I make pretty things,” and leading to the “question of being the other; of portraying myself, sometimes naked, and how is it feminist.” In response, Goico doubled down on the feminine and craft-based aspects of her work, producing the aforementioned 'Pelliza Total' (with cunt).

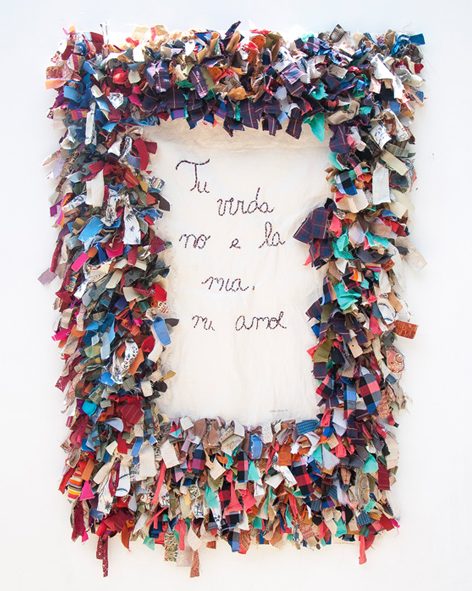

These questions tended to become cast in a cultural light as well. “One of the issues that came up was the idea that really crafty things was a dumbing down,” she recalls. “When you are a conceptual artist craft is look down, like 'Ugh, why do you waste your time on it?', and that's what I always felt—the judgment that these people from the Dominican Republic are all crafty-dafty but they don't have the brains.” Goico's answer was a pelliza with the notice “Your truth is not mine” woven in the middle.

“Let's just make imagery,” she remembers thinking to herself. She turned to a self-described naif style of painting, using imagery from both Voodoo sources and Catholic saints, and using rescued pieces of board. “I was trying to decolonize my own artistic upbringing,” with its emphasis on Western art practices and fine finishes. “I wanted to divorce myself from that, and bring myself back to those non-Western concepts of what is pretty, what is visually appealing, what are the colors that we use.” Her Parsons thesis was on syncretism, religious practices of Taino people (the indigenous culture of the Caribbean and Florida), and sexual narratives—“that was my fuck you, Conceptual art.”

Bright colors, self-portraits, and Goico’s ethnicity often led to Frida Kahlo references, a lot of them. “All the time,” Goico says, not unflattered but aware of the reduction of her work such a comment reflected, rather than a critical assessment or real compliment. “I knew this would be the tough part of my art-making, getting past the first thing: I'm a Latina artist, doing self portraits mostly and doing ethnic things. My practice was disregarded; it became, “Oh yeah, you're talking about your culture, got it, we've already dealt with that.” Latina, feminist, naif, political, social practice—the labels swiftly applied to Goico’s work and to her, mounted, defining, otherizing, while shaping her own view of the art world. “I don’t mind anymore,” she says, “I’ve understood here that unfortunately you will be put under labels, not matter who you are, where you’re from—unless you’re a white cis heterosexual man. That is the only way you won’t be categorized.”

That kind of realization has allowed Goico to strive for different goals within her practice: “I don’t feel that the problems of the art world are that relevant to me. I know there are so many problems in being a person of color in the art world, but I think there are so many issues outside of the art world that I would rather address. It is the outside where people are getting killed.”

(to be continued...)

Gina Goico recently relocated her multidisciplinary practice to Los Angeles, and continues to work with Dominican culture and politics in diaspora and the Dominican Republic.

Emma Drew is currently completing her MFA in Art Writing at the School of Visual Arts. She lives and works in Brooklyn.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Spanish Translation:

La contribuidora de EAS, Emma Drew, recientemente visitó a la artista Gina Goico en su estudio/apartamento en Manhattan, donde Gina habló sobre su práctica artística y su experiencia como artista Dominicana en los Estados Unidos.

En los dibujos las pellizas cuelgan pesadas; alfombras gruesas caen en cascada desde la pared hacia el suelo, un diluvio de telas coloridas. Estos son planos para un nuevo proyecto. Las pellizas ya realizadas están llegando allí; cubren las paredes, los muebles, la parte de atrás de una silla, el radiador bajo la ventana en la sala de Gina Goico. En sus años en la facultad- no hace tanto- los tapetes hechos a mano, en tela de saco o lona plástica, y pedazos de tela (todos estos usualmente siendo reutilizados), llevaban un mensaje desafiante, o la ilustración estilizada de una vagina ---”sacar el dedo del medio,” ella califica con una sonrisa, a la estrechez de mente de la escuela de arte. Hoy en día, aún cargadas de testimonio femenino, estas capturan historias contadas en el espacio y tiempo que se realizan, de otras mujeres.

El proyecto Pelliza, donde Goico invita a otras personas a unirse a tejer cuando esta se localiza en lugares y eventos públicos (previamente destacado en EAS: Aquí), fué concebido no sólo como la creación de un objeto tradicional, decorativo o utilitario, sino más bien como un lugar para la mujer y espacio para conversación. Cuando se performó en un colmado en Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, su ciudad natal, estas conversaciones pronto tomaban un tono personal; pláticas sobre relaciones e historias sobre violencia doméstica. “Salían naturalmente,” Goico cuenta, sobre las experiencias cotidianas de violencia por esposos, amantes y hombres en la familia. La República Dominicana, ella observó, tiene uno de los más altos índices de femicidio --(asesinato de mujeres por razones de género)-- en la región; no hace tanto el país ocupó los primeros 10 lugares en el mundo. Proveyendo la oportunidad de hablar, Goico quiere “guiar la conversación sobre los espacios seguros para mujeres.”

Aparte de las Pellizas, el apartamento-estudio de Goico está repleto con otra evidencia de su práctica: cuadernos repletos de bocetos, pinturas de sus días en Parsons La Escuela de Diseño, y carteles promocionando sus performances de carácter social, uno con las imágenes de los clubes Dominicanos los cuales ella critica como espacios de machismo y explotación femenina. Se ven de pared a pared rastros de componentes y pasos para el establecimiento del largo y gran proyecto #ATABEY (Hashtag ATABEY), una iniciativa de investigación, programas de alcance comunitario, instalaciones, performances, discusiones y plataforma para discutir las políticas de feminidad e interseccionalidad - esto es siendo una mujer y muchas otras cosas- en la República Dominicana y sus diásporas.

Lo que se ha convertido en algo bastante conceptual en naturaleza y en aspiraciones fué inicialmente una contra mesura a esta manera de pensar sobre arte. Cuando Goico se mudó a la Ciudad de Nueva York a terminar su Licenciatura en Bellas Artes en Parsons, la línea de pensamiento conceptual ejercida por los profesores y debidamente seguida por estudiantes se le presentaba a manera de alto contraste en comparación a la tradicional escuela de Bellas Artes a la cuál asistía en la República Dominicana donde, por ejemplo, dibujo hiperrealista y belleza pulida eran prioridad. La transición al mundo del arte en Nueva York muchas veces significaba una confrontación entre imágenes e ideas, una dicotomía falsa a la cuál Goico admite ella respondía fuertemente. Su trabajo en este momento, incluyendo su primera Pelliza, era “un poco reaccionario en cuanto a lo que estaba enfrentando, comenzando por la pregunta de porqué hacía cosas ‘bonitas’” y conduciendo a “cuestionamientos sobre ser el otro; de estar retratándome, a veces desnuda, y como esto es feminista.” En respuesta a esto Goico extremo en lo femenino y en el aspecto artesanal de su trabajo, produciendo así la anteriormente mencionada Pelliza Total (con coño).

Estas preguntas solían cargar consigo un tono cultural también. “Una de las cuestiones que surgieron era la idea de cómo objetos que requerían trabajo era un embrutecimiento,” ella recuerda. “Cuando eres un artista conceptual, la labor manual es menospreciada, como ‘Ay, por qué estás perdiendo tu tiempo en esto?’, y así fué como me sentía- el pensamiento que esta gente de la República Dominicana poseían el artificio pero no el cerebro.” Goico respondió a esto con una pelliza que lee “Tu verdad no es la mía” bordada en el medio.

“Vamos a hacer imágenes”, ella recuerda pensar para sí. Ella comienza a hacer pinturas auto denominadas naif, usando imágenes de santos de origen Católico y Vudú, y reusando pedazos de madera. “Trataba de descolonizar mi propia educación artística,” con un énfasis en prácticas artísticas Occidentales y terminación refinada. “Quería divorciarme de eso, y traerme de vuelta a esos conceptos no-Occidentales de belleza, lo que es visualmente atractivo, los colores que utilizamos.” Su tesis en Parsons fue basada en sincretismo, prácticas religiosas de los Tainos (cultura indígena del Caribe y la Florida) y narrativas sexuales- “ese fué mi vete a la mierda, arte Conceptual’.

Colores brillantes, autorretratos, y la etnicidad de Goico frecuentemente llevaban a referencias de Frida Kahlo; muchas. “Todo el tiempo,” Goico dice, no sintiéndose ofendida pero consciente de la reducción a su obra que comentarios como este reflejan, más que una crítica o cumplido. “Sabía que esto sería la parte difícil de crear arte, poder pasar esa primera barrera: Soy una artista Latina, creando mayormente auto-retratos y haciendo trabajo con contenido étnico. A mi práctica se le hacía caso omiso; se convertía en un ‘Ah sí, estás hablando de tu cultura, entiendo, ya hemos lidiado con eso.’” Latina, feminista, naif, política, práctica social- clasificaciones rápidamente aplicadas al trabajo de Goico y a su persona, montadas, definiendo y exotizando, mientras definian su propia visión del mundo del arte. “No me importa tanto ya,” dice ella, “He entendido que aquí lamentablemente siempre vas a existir bajo estas etiquetas, sin importar quien eres, de donde eres- a menos que seas un hombre Blanco cis- heterosexual. Esa es la única manera que no serás clasificado.” Esta realización ha permitido que Goico se esfuerce por otras metas dentro de su práctica: “Yo no siento que los problemas del mundo del arte sean relevantes para mí. Sé que existen muchos problemas en ser una persona de color dentro del mundo del arte, pero creo que hay tantos problemas fuera de este que yo prefiero discutir. Es allá afuera donde se está matando a gente.”

(continuará)

Gina Goico recientemente trasladó su práctica multidisciplinaria a Los Ángeles, y continúa su trabajo con cultura y política Dominicana en la diáspora y la República Dominicana.

Emma Drew está actualmente completando su Máster en Escritura Artística en the School of Visual Arts. Ella trabaja y vive en Brooklyn.