Teaching art to kids in a remote Indian village | Final episode

Responses to Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’ and to the Surrealists’ paintings, together with some great lessons on how to introduce art to young people.

[Read Episode 1 and Episode 2 in the same 'Convesations' page of the website]

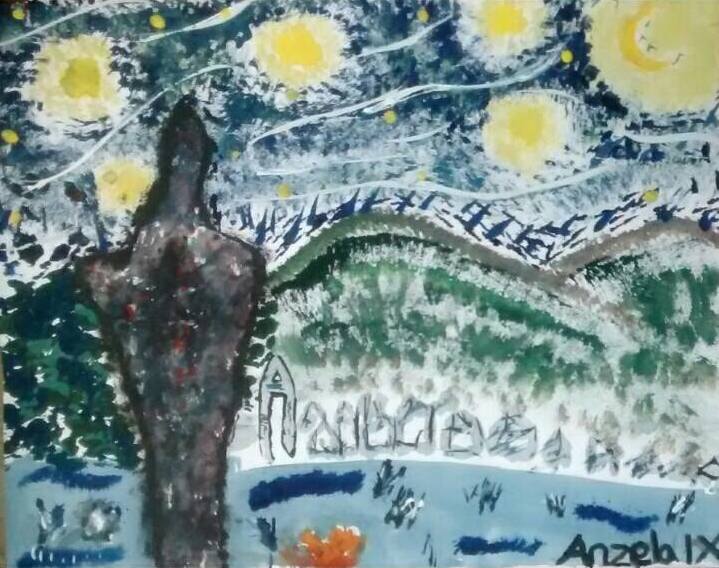

In order to draw all grades students’ attention to bright and vibrant colors I decided to focus on Van Gogh’s work. The idea was to introduce the painter and some of his works, to teach them about his techniques, and then to try a hand-on practice of those techniques, using their own emotional intensity while painting. I chose ‘Starry Night’, one of his most famous paintings, distributed some prints, and asked them to follow any one of these two options:

In order to draw all grades students’ attention to bright and vibrant colors I decided to focus on Van Gogh’s work. The idea was to introduce the painter and some of his works, to teach them about his techniques, and then to try a hand-on practice of those techniques, using their own emotional intensity while painting. I chose ‘Starry Night’, one of his most famous paintings, distributed some prints, and asked them to follow any one of these two options:

paint the same composition of ‘Starry Night’, although with their own style of brush strokes, or create their own composition, but using the same thick and broken brush strokes as Van Gogh did in the painting.

It seems to me that each work has a stunning balance of composition. I still don’t understand how they got those perfect balanced composition. What I feel is that when a blank paper is given to a kid, together with some materials to draw or paint on it, he or she become the master of that sheet of paper, and more responsible to dominate that blankness. Maybe that’s when they bring out their creative side.

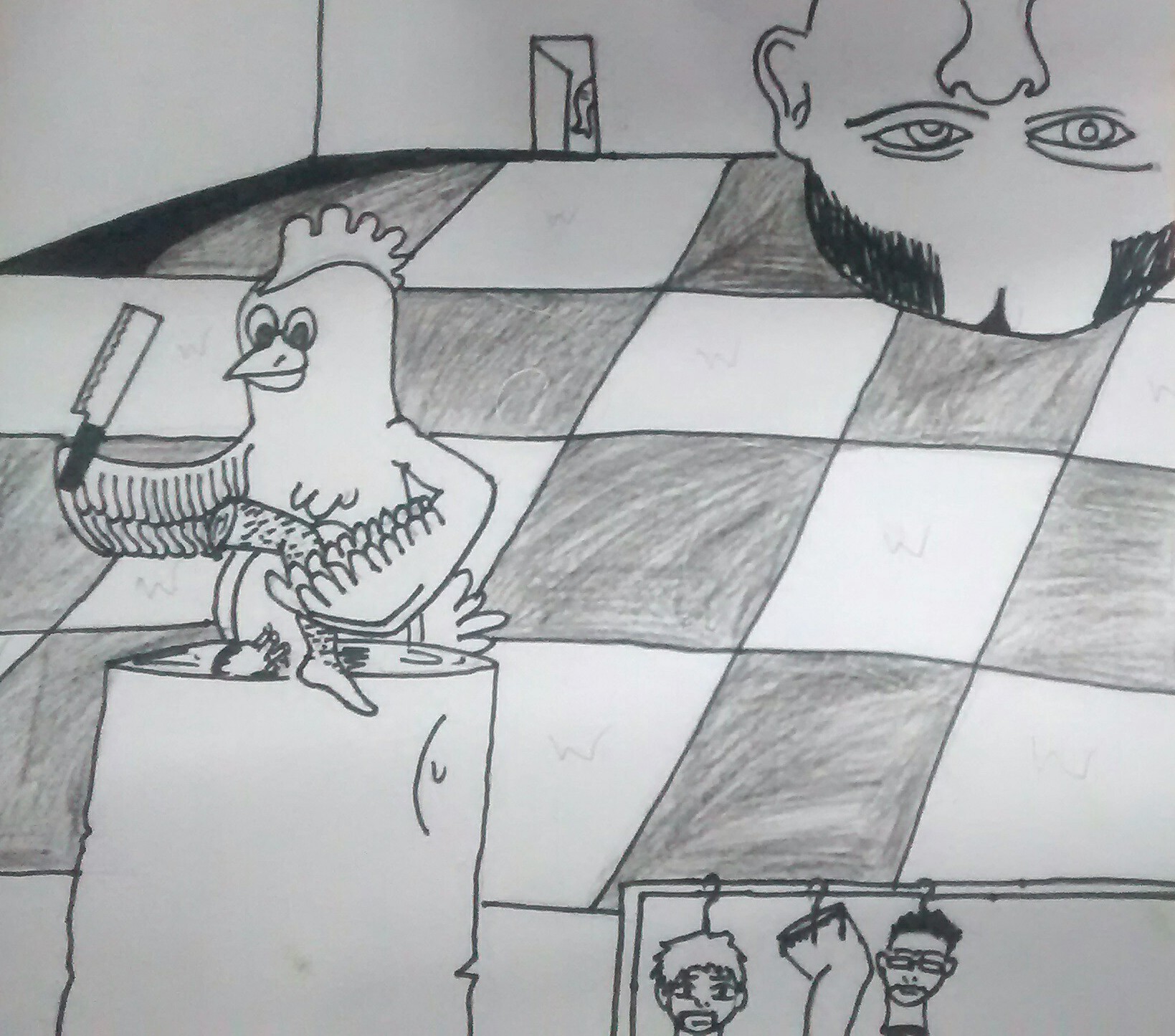

Another project was on Surrealism. I explained Surrealism as an artistic as well as philosophical movement that focused on dreams and the subconscious mind, rather than on logical thinking, as a way to find truth. I shared with the students the works of surrealist artists like Joan Miro, Salvador Dali, GIorgio De Chirico and Rene Magritte.

They particularly loved the works by Dali and Magritte, maybe because of the use of realism to show the subconscious  I shared with them the knowledge of simple landscapes, compositional elements such as foreground, background and middle ground. Students begun by participating in a discussion of the imagery found in one of Dali’s painting. They were encouraged to give their own interpretation of the imagery while pointing out any device that was used to make the image surreal. Students were asking questions, like “How does Dali make it clear that these were representations of subconscious images?” “Is the use of realism important in conveying mood?” as well as questions about what elements they might include in their works, etc.

I shared with them the knowledge of simple landscapes, compositional elements such as foreground, background and middle ground. Students begun by participating in a discussion of the imagery found in one of Dali’s painting. They were encouraged to give their own interpretation of the imagery while pointing out any device that was used to make the image surreal. Students were asking questions, like “How does Dali make it clear that these were representations of subconscious images?” “Is the use of realism important in conveying mood?” as well as questions about what elements they might include in their works, etc.

This exercise must have been challenging. It has compelled me to realize how young adolescents understood and vividly represented what the surrealist artists disguised and hid in “absurdity”. Your students really showed the pain and human suffering. They teach us how to see what we avoid to see…

Each and every project we did came up with new dimensions. The bold vibrant use of color, the emotional outbursts while recreating starry night, the confident brush strokes while recreating Patachitra, the absurdity of imagination while creating the subconscious can only come out from a child’s mind.  If we look at the project on surrealism we can see that each and every work has a different story to tell. I realized that every student tried to understand the idea of the subconscious and the method to dig up surreal images.

If we look at the project on surrealism we can see that each and every work has a different story to tell. I realized that every student tried to understand the idea of the subconscious and the method to dig up surreal images.

I am curious about how you balanced the information about Eastern and Western history of art? How did this information, above all that regarding new techniques, stimulate or affect the students’ initial visual knowledge?

As I joined the school, I was initially asked to structure the entire art syllabus for the academic year. After communicating closely with the students, I discovered that introducing another subject, namely art history, was going to put an extra burden on an already intense curriculum. I noticed their highly regulated routine, and I didn’t want to introduce myself as an another art history teacher.

I thought that rather than introduce them to the vast chronological history of both Western and Eastern art in terms of styles and historical, geographical features, I should introduce a little free space, away from their regular routine. I wanted to set our class not to be ruled by the demonic figure of “Knowledge”, descending “from me to them”, but to provoke, and generate amusement and curiosity “from them to me”.  As an introduction to art and to what art is, my goal became to introduce them to the varieties of visual arts, their nature and differences, their strength of expressiveness, and their the language of freedom.

As an introduction to art and to what art is, my goal became to introduce them to the varieties of visual arts, their nature and differences, their strength of expressiveness, and their the language of freedom.

I wanted the students to get glimpses of different achievements in the history of visual arts in a way that would be accessible and could fit their own language of expression, to be curious about each and every art movements rather than imposing on them heavy art history books. My pedagogical strategy was to find the order and balance through their curiosity and the hunger for knowledge.

Since their knowledge of visual art was very narrow according to the standards set by the Indian academic colonial past, their concept of art was based on only one scheme or style.  The traditional art forms of their culture are still not considered art, but rather ritualistic, cultural religious practices. My first task was therefore to break that notion by introducing various artistic styles from different times and places.

The traditional art forms of their culture are still not considered art, but rather ritualistic, cultural religious practices. My first task was therefore to break that notion by introducing various artistic styles from different times and places.

The initial reaction of many students was “Is this also art?” and “Can art be made like this?” This gave them enough encouragement and confidence to be creative. The courage they got was to explore other ways, without worrying about preset notions of British academic art. Those, for example, who feared to play with colours because their association with British naturalistic landscapes oil paintings, got a lot of encouragement by the raw use of colour of Van Gogh, or the playfulness of colour dots by Seurat. As everybody knows, every child is born with creative impulses; each new technique, therefore, and each new visual language, provoke their creative intuitions.

I know that probably none of my student will become a professional artist. Some will be doctors, or lawyers, philosophers or teachers, or any other profession, but some training on the great stories in the history of visual art can change their perspective, make them better viewers and more concerned individual.